Kanji Recognizer as a self-teaching tool

Kanji Recognizer as a self-teaching tool

How to write kanji is a question that Cure Dolly would precede with another question, namely whether to write kanji. As a matter of fact, I am largely of her school. Like Cure Dolly, I hand-write maybe two dozen words a year in English. So why do I want to learn to do in Japanese what I don’t even do in English?

The arguments over whether you need to learn how to write kanji in order to learn kanji at all are discussed by Cure Dolly, and I am broadly in agreement. It depends on who you are, what your needs are, and how you learn best.

But let’s say you are like Cure Dolly (and I am). Let’s say you don’t need to write kanji (for exams or whatever) and you only need to recognize them for purposes of both reading and (electronically) writing. Is there any need to learn to write them at all?

I really don’t see any value in sitting down to write kanji hundreds of times. I have heard people complain about doing this and still finding the kanji to be strangers to them in a week or so.

I actually am learning a tiny bit to write kanji, but none of them are strangers to me. I know the kanji. I am familiar with their components. That isn’t the point of writing them to me. So what is it?

One thing I have realized is that while my recognition is reasonably good, my ability to picture shapes is (perhaps abnormally) terrible. I can read hiragana with no problem, but I recently realized that I could no longer write several of them. I did learn them in the beginning and could write them easily. I found that a year or so later, even though I had no trouble at all recognizing them and reading them, I don’t actually remember how they are made up. I can’t picture them in my head. I only know them when I see them.

I am not saying this is necessarily a bad thing. Personally I don’t want to lose my ability to hand-write kana, so I did a little practice with a kana-writing app just to get it back. If I wrote anything by hand—shopping lists, anything—I would do it in Japanese just to keep my hand in. But I don’t. I am a near-total non-writer.

However, kana is not the point here. The point is kanji. What I have found there is similar. Since I didn’t know how to write kanji, I didn’t really know how they were made up. I didn’t really know the difference between 家 and 象, for example. I tended to recognize them by context rather than their actual differences. I don’t think learning to write kanji is the only way to overcome this problem. One could just familiarize oneself more firmly with the components of each and make up little stories around them, which is how I learned them in the first place.

One of my problems with writing is a pathological fear of paper. I really can’t manage the stuff. If you start allowing it into the house it gets everywhere—but you can never find the bit you want. I really can’t start toodling around with bits of paper. For me it would open the door to nameless chaos.

But I did start to feel it would be worthwhile to write kanji. Not hundreds of times—just a few times each. Not in order to learn them—the kanji I write I already know by sight—but simply in order to clarify my mind on their exact composition.

And it works. But you really need the right tool. Fortunately I found it. It is called Kanji Recognizer. It is an Android app. You can write the kanji with a stylus on your tablet or keitai. Although this is not the purpose of the software, what it does is both allow you to write kanji (without all that scary paper) and act as an instant tutor at the same time.

Let me show you how:

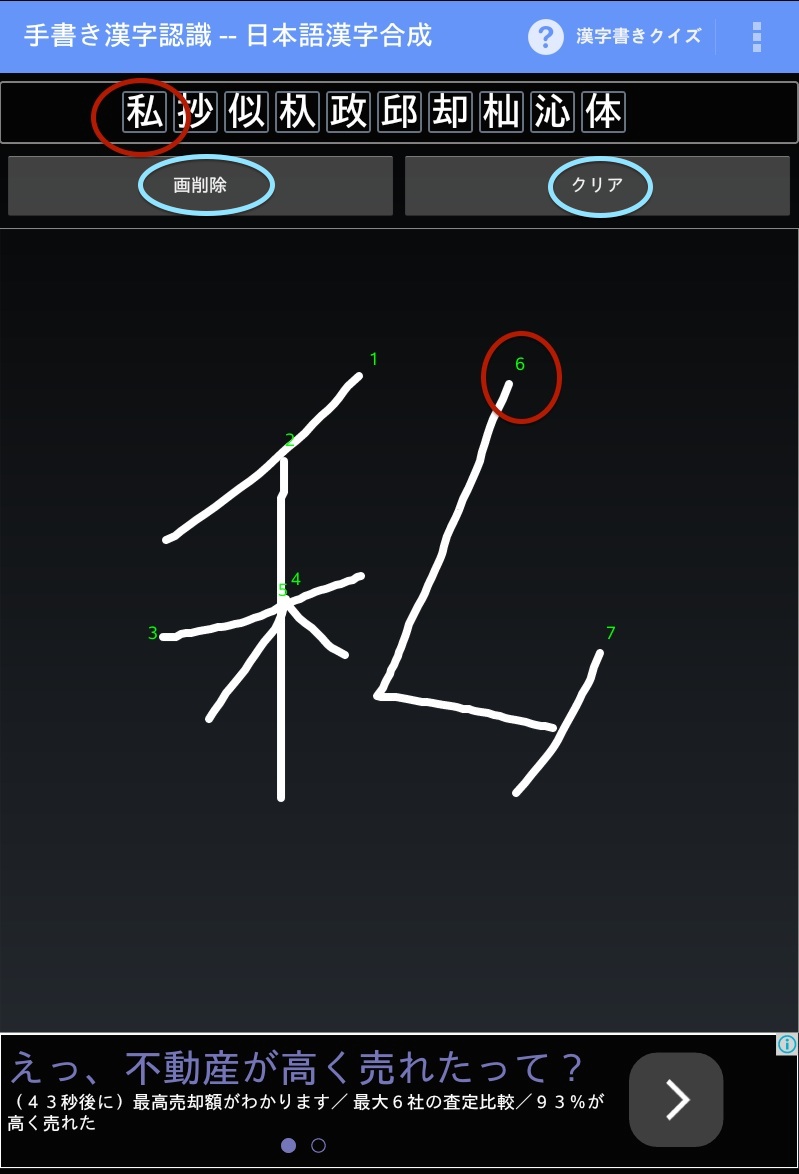

You write the kanji freely, and as you can see, Kanji Recognizer tries to work out what you wrote and places its top ten guesses along the top. The higher you come in the top ten, the more accurately you have written the kanji. This in itself is very, very useful.

The software also numbers your strokes, so you are able to check your stroke order. It puts the number at the start of each stroke so you can also check the stroke direction (this comes into its own later as you will see).

The two buttons ringed in mizuiro (pale blue—I don’t know why there isn’t an English word for the “pink” of blue, but there isn’t) are 画削除 kakusakujo (delete stroke) and クリア (clear). 画削除 is very nice as it allows you to get rid of strokes you messed up. Paper is just mean about that sort of thing.

The app is free, though ad-supported. If you have your device in Japanese (and you should) the ads will tend to be Japanese too, as you can see at the bottom of the screenshots.

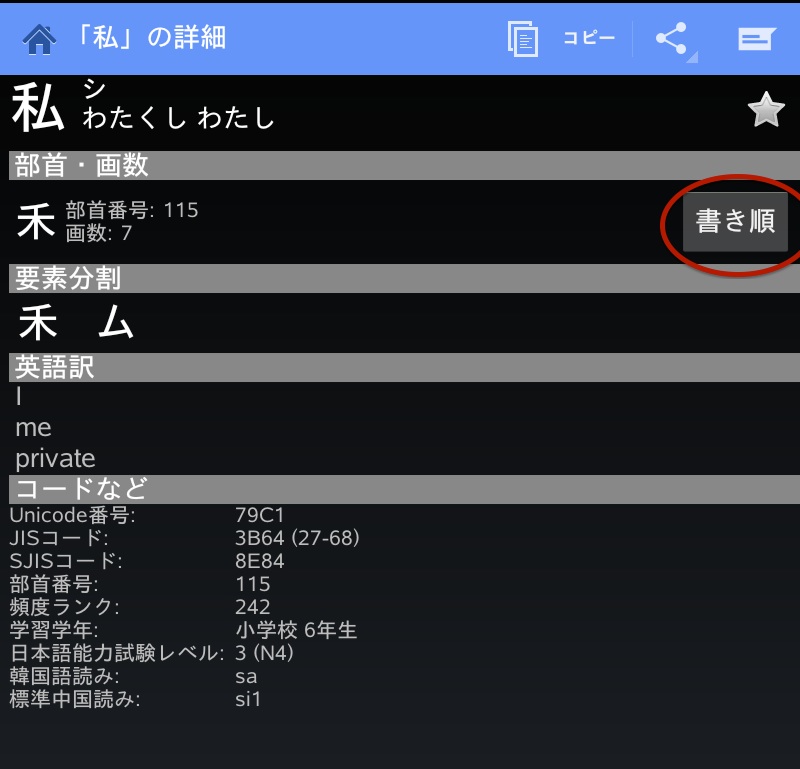

Once you have written your kanji, you can tap the correct one at the top to get a screen of information about it:

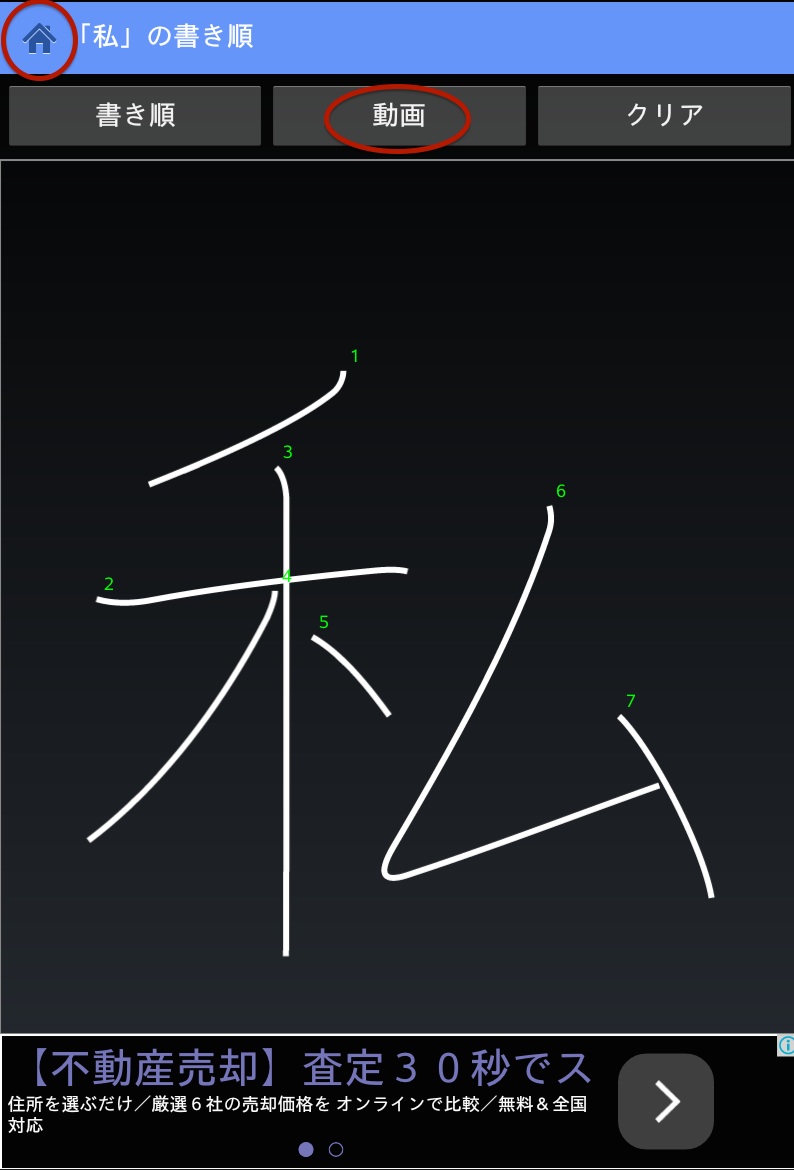

This, of course, is immediately useful for making sure the kanji is what you thought it was! The most important thing here for our purpose is the button we have ringed: 書き順 kakijun (writing order—or stroke order, as they tend to say in English). This gives you, as you might expect, an image of the kanji (written with an enviably steady hand) with its correct stroke order marked:

This, of course, is immediately useful for making sure the kanji is what you thought it was! The most important thing here for our purpose is the button we have ringed: 書き順 kakijun (writing order—or stroke order, as they tend to say in English). This gives you, as you might expect, an image of the kanji (written with an enviably steady hand) with its correct stroke order marked:

However, the really useful thing here is the (ringed) button labeled 動画 douga (animation). Press this and the app will clear the kanji and re-draw it for you, so you can watch it forming stroke by stroke and see how it is done.

You can then click the home button (ringed) which will take you back to the page where you wrote the kanji originally. It will still be there, just as you wrote it, so you can check whether you had the stroke order and direction right. If you didn’t make number one in the top ten, you can hit クリア and try again.

If you have an idea of the general rules for stroke order, you will get it right a lot of the time. The surprises will tend to impress themselves on your mind. The animation is particularly useful for this, I find. What you will also start to find instinctively is a lot of kanji-order sub-rules. They aren’t taught and rightly so, as they are fiddly and have exceptions, but they do start to make a kind of sense in practice, I find.

I am still not really trying to learn how to write kanji. I know hand-writing is never going to be a part of my real life. Actually, I would like to learn Japanese calligraphy one day, but that is something of another matter. What I am finding is that this gives me a better feeling for how the kanji work, how they hang together.

My method is perhaps unusual. I have never in my life “learned a kanji”. I learn words as I go along, and I make friends with the kanji that form them. People have occasionally asked “how many kanji do you know?”. I have no idea how to answer. How would I know? Maybe some people go through a book from Kanji 0001 to Kanji 2500, but I really wouldn’t even know how to do that, and I am sure it wouldn’t stick that way.

When I write kanji on my little slate, I am already friends with those kanji. I have known them for some time. Now I am taking tea with them and learning their funny little ways. I am a horribly inattentive friend, and there are so many things about them I never noticed. I love them so I want to learn.

If you love something, you should pet it. Kanji recognizer was essentially made to be a dictionary, not a tutor. It works as a tutor, and (for me at least) as something else too. It is my favorite Virtual Pet game!

Oh how interesting! After the holidays, I might have to investigate the App. Right now, I am working with a first grade kanji workbook, which is really interesting.

When I was watching a Yes! Precure episode, the adventure of the week started by a fairy who wanted to learn to write novels, and in preparation, she copied a book by hand (which happened to be Cinderella). All of the girls (and the senpai fairies) agreed that copying a novel by hand was a good way to learn how to write novels. Isn’t that curious?

From this and other things I have seen in Anime, there seems to be a notion that writing by hand is important for much, much more than just learning the kanji.

Heee…sorry about the blather….and I do understand your difficulties with paper (I have paper monsters myself).