There are a lot of kanji-learning systems around these days.

There are a lot of kanji-learning systems around these days.

But what if the best system is no system?

Our method of learning Japanese is based on a minimum of abstract study and a maximum of immersing yourself in the language and really using and enjoying it.

But what about kanji?

Why they say you can’t learn kanji organically

On the face of it, there is a strong case against the possibility of learning kanji organically.

Children don’t learn to speak their own language out of textbooks. Their grasp of grammar and vocabulary comes from hearing it and using it. Before they learn to read, they already have a grasp of vocabulary and grammar that takes a foreign student years to acquire.

See a more up-to-date version of this article in this video:

But writing is different. No one acquires the alphabet naturally. They actually have to sit down and learn it. Kanji is the same, only several hundred times bigger. Japanese children study kanji in school for years before they become fully literate. So what is this talk about learning kanji organically? Surely they have to be learned by an abstract system. Even Japanese people learn them that way.

The answer to this is “yes, and no”. Japanese children do learn kanji as kanji. But they already know the words that they signify. They are not learning them in the abstract. The minute they learn a kanji, it attaches to a body of knowledge they already possess and becomes a living part of their language understanding.

This is why we say, “learn words, not kanji”. Which is to say, learn words with their kanji. And learn vocabulary not from vocabulary lists, but from organic encounters. We have already discussed how to build vocabulary organically. This article is tackling the question of how to learn kanji as a part of this process.

It is largely because of kanji that we recommend using Anki. You can learn vocabulary purely organically, but you do need to drill kanji, and, if you don’t need to write kanji, then Anki is in our opinion the best way to learn vocabulary and kanji at once. This gives you the basic minimum of drilling that you absolutely need, and makes it do double duty for kanji and vocabulary.

However, we aren’t going to talk about Anki here, but about the actual strategy for breaking down and remembering the kanji.

Remembering the Kanji (without the system)

James Heisig’s book Remembering the Kanji has been hugely influential in showing people how to see kanji as picture stories rather than abstract patterns of strokes. Some people seem to think Heisig-sensei invented this technique, but as he makes clear in his introduction, he didn’t. What he did was to systematize and popularize it.

Since then other people have made systems with the same general principles. What we do is to de-systematize it.

Why?

Well, it depends on how you learn and what you want to do. Some people want to spend a long time systematically learning kanji. We wanted to spend that time acquiring Japanese by immersing ourselves in it, with kanji as one of the things we pick up as we go along.

How to Learn Kanji Naturally and Organically

So without more ado. This is how to actually tackle kanji.

From early on you will be aware of the pictographic nature of some of the simpler radicals and kanji, and how they combine to form concepts. For example:

早 quick/early (a kanji in itself)

⺾ plant (not a kanji but a common kanji element)

草 grass (⺾ plus 早), which is the earliest, most basic, (and quickest growing) of plants

When you look at the most common kanji elements in Wikipedia, you learn that 30 of them make up 70% of the common use kanji (this figure seems a little exaggerated to me, but the principle is true).

So what you are going to do with kanji is work out what they are made up of, and see how the elements fit together. Sometimes you will see a very logical and obvious meaning. Sometimes you will be making up a far-fetched mnemonic story to tie the elements to their meaning.

So how do you know what elements a kanji is made up of?

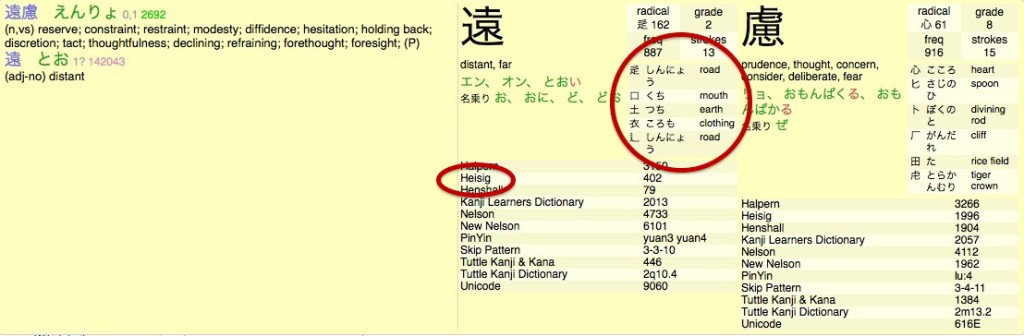

There are various methods you can use. You may indeed want to browse books such as Heisig-sensei’s or other kanji memory books. There are lots of resources online such as Kanjialive’s list of the 217 traditional radicals (traditional names and meanings) and Toufugu’s kanji radicals cheat sheet (somewhat fanciful). The quickest, simplest, on-the-fly tool is the search box on Rikaisama‘s toolbar (you can embed the search box on your browser without having the whole toolbar). This gives results like this (click to enlarge):

[UPDATE: Rikaisama no longer exists, but you can get the same box by pressing return when a Rikaichamp definition box is open]

[UPDATE: Rikaisama no longer exists, but you can get the same box by pressing return when a Rikaichamp definition box is open]

As you see, this gives a breakdown of the elements in each kanji (ringed) when you look up a word. Another interesting feature is that the Heisig reference (ringed) is a link that will take you to the Reviewing the Kanji site, a user resource where people share their Heisig-based mnemonic stories for the kanji.

This latter can be useful, but I recommend using it with caution. Let me explain why, because it will make clearer how organic kanji learning works.

The Heisig system gives a unique English keyword to every kanji and kanji element. It has to do that because in this system you need to know from the keyword exactly how to write each kanji. This is done without knowing the meaning or pronunciation of any Japanese word. As a result there are some pretty strange and sometimes dubiously relevant English keywords.

Now we aren’t doing this. We aren’t associating kanji with English keywords, but with actual Japanese words.

Let’s take a complex example. When I see 蕩 I think torokeru (which is the main word in which it is used. I know it means “melt” both in the sense of a solid melting into a liquid and a heart melting (becoming charmed or enchanted). A Heisig student is simply trying to associate this kanji with the Heisig keyword “Prodigal”(!).

Now if we look at the elements of this kanji we get a clearer idea of how our organic approach works. The elements are⺡the water side-element ⺾ grass/flower 日 sun and 勿 piglets.

Now in our eclectic way I do owe something to Heisig-sensei here 勿 is in fact a diminutive of 豕 the pig element and since small pigs can be piglets, well that’s kind of cute so we borrowed it.

But here is where we diverge. When you put 日 on top of 勿 you get 易 to which Heisig-sensei gives the keyword “Piggy Bank”. (Piglets you put money in every day – 日 sun can also be day).

All right you can make stories out of this and Heisig-sensei is forced to do this sort of thing because his system demands exclusive keywords.

But 易 is actually a fundamental element which refers to the light and warmth of the sun. If you need a mnemonic just think of the bright sun warming the dear little piglets basking below.

Let’s see how 易 the sunshine-component works in some more complex kanji:

A very frequently used word for the sun is 太陽 taiyou (kanji elements: 太=great, 易=warmth/light, coming over the ⻖=hill).

陽 alone is the word for yang (which refers etymologically to sunshine as opposed to yin, shade).

湯 is hot water (⺡=water plus our 易 sun-warmth).

場 is a place – originally and still usually an outdoor place: thus a piece of earth 土 out in the sunshine 易.

We really don’t need to bring Piggy Banks into any of this. It may be necessary for producing a unique English keyword, but it disrupts the natural conceptual symbolism of the kanji element.

To return to 蕩, we can now see how hot water (湯) may melt many solids, but it leaves everything with the loving, enchanted scent of flowers (⺾). We don’t need keywords, but we do need the right concepts.

So if we don’t verbally associate kanji and their elements with keywords, what do we associate them with? Usually with the first word we learned them in, or the word we most commonly associate them with. I think of 正 as “the kanji of tadashii” (right, proper, correct) although it is used in many other places with related meanings but other pronunciations (for help with those pronunciations, meet the Sound Sisters and discover that 正 is a sei/shou sister).

We also tend to remember elements by the word we first or most often encounter them in. So, for example the left side of 優 (the kanji of yasashii, gentle) is actually 愛 (the kanji of ai, love) with the ⺤ replaced by ⾴ (head, page. Bottom element merged). So we have a person with head as well as a loving heart. This kanji as well as meaning gentle, can also mean actor/actress or superior/best. You see how a single keyword is not entirely adequate!

As we develop our knowledge of the kanji by meeting it in other words, we develop also our mnemonic associations. The person with loving heart as well as a good head on her shoulders is not only gentle, she is the best. And having both intelligence and warmth makes her a great actress.

Sometimes actual mnemonic stories are helpful. For example, do you know why human bodies float? When the first child fell in the water she sank like a stone, but was pulled up by Tsume-chan, the kind crane-game-type claw. Ever since then, the invisible claw has always made human bodies float. 浮くuku, to float, is made up of water, claw and child.

You will be making your own meanings out of the kanji elements. Incidentally, after hand-holding through the first few hundred kanji, Heisig-sensei also leaves students to make their own stories out of his keywords, and rightly so, as the mnemonics we make for ourselves stick best.

The difference is, that instead of using artificial, and often eccentric, keywords, you will be learning kanji not as abstractions but as part of the living language as you make friends with words and their symbols and build your vocabulary organically.

While かんじ is difficult to learn, I find the pictographic writing system to be fascinating. It’s like telling a story as you draw, rather than just words on paper. That’s deep, and that inspires imagination, I believe.

> It is largely because of kanji that we recommend using Anki. You can learn vocabulary purely organically, but you do need to drill kanji, and, if you don’t need to write kanji, then Anki is in our opinion the best way to learn vocabulary and kanji at once. This gives you the basic minimum of drilling that you absolutely need, and makes it do double duty for kanji and vocabulary.

It seems like you are saying that you cant learn kanji organically. Certainly, drilling them with Anki is not what I would call organic.

But I have been wondering whether kanji dont actually make it harder to understand spoken Japanese. I guess that Krashen’s “massive amounts of comprehensible input” method isnt based on experience with logographically written languages.

Listening comprehension involves understanding Japanese from just the phonemes. It seems like reading books with only kana would be better practice for this.

Yes, I am saying that I don’t think kanji can be learned organically in the same way that spoken language can. Neither can the alphabet, but that is a much smaller undertaking.

However kanji-learning can be part of an organic approach to Japanese, by which I mean that we learn kanji as part of an understood language, and as relating to words that we know and use, which is what Japanese children do. This is very different from the Heisig approach, and (to a lesser degree) from kanji-learning books in general.

From my experience I would say that kanji do not make spoken Japanese harder to understand, in fact quite the reverse. Japanese has a much more limited range of sounds and possible syllables than most languages, and one quickly finds oneself to some degree “thinking in kanji” when listening to Japanese. “Oh, it’s that sou” etc. This is also how Japanese people think of spoken language (they sometimes draw a kanji in the air to clarify an ambiguous word).

Small Japanese children, of course, acquire a limited (but comparatively large) vocabulary purely by sound, but I think beyond a very simple level, spoken language and kanji are so closely bound up in the way the language is structured that one really needs to have a good sense of both.

I do not believe that reading books in all-kana would help with listening. Reading indirectly helps listening by broadening one’s vocabulary and giving one a sense of the way things are said and which words habitually belong together (because effective listening works in chunks, not word-by-word).

I would say that this works better with text written the way it is normally written (because kanji are a structural part of the language and help one’s sense of how it all fits together). But the main thing that helps with listening is listening.

Yeah, I was just a bit disappointed since the title suggested otherwise.

I think that learning kanji might make more sense when my vocabulary is larger.