As you probably know, the word あたたかい atatakai (warm) can be written in two different ways: 温かい or 暖かい. Is there a difference between them?

Yes there is, and actually it is a fairly obvious one, but I think it is a little less well known to learners than similar differences in other temperature-words.

Of course you know, unless you are a very early beginner, that there are two words for cold: 寒い samui, which means cold weather or ambient temperature, and 冷たい tsumetai, which means a cold object, cold hands, a cold drink etc.

You probably also know that there are two forms of あつい atsui (hot), which correspond directly to the two words for cold: 暑い (atsui with a double dose of sun) is hot weather or ambient temperature, 熱い (atsui with a fire under it) is a hot object.

So it isn’t too surprising to learn that atatakai does the same thing – though not quite as absolutely.

暖かい usually means warm weather or ambient temperature. I see this one as 爪 tsume–chan lifting her 友 friend into the warm 日 sunshine.

暖かい usually means warm weather or ambient temperature. I see this one as 爪 tsume–chan lifting her 友 friend into the warm 日 sunshine.

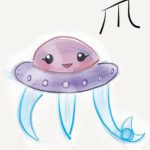

Oh – you haven’t met tsume-chan yet, have you? Some day I would like to do a book introducing my personal kanji-element characters. Tsume-chan is the 爪 element – a happy UFO-catcher claw who rescues her friends from all kinds of danger. For example, she helps 子 children 浮 float when they fall in the 氵water.

She looks like a UFO because she works in a UFO Catcher when she isn’t out on rescue missions.

She looks like a UFO because she works in a UFO Catcher when she isn’t out on rescue missions.

Anyway, enough of that. I do love my characters!

The only other thing to remember about 暖 is that its usual on-reading is dan, as in 暖房 danbou (interior heating) and 暖炉 danro (hearth fire).

温かい is more prone to mean a warm object, warm water etc. From the kanji, warm water might seem to be a primary meaning. It is easy to remember that the 日 sun warms 氵water in a 皿 dish .

The on reading of 温 is on. Easy to remember if you think of 温泉 onsen (a warm-water spring or spa).

The two atatakai forms are not as absolutely distinguished as samui and tsumetai, and there is some crossover between them. 暖 especially seems to cross over into the area of things that warm the body, like a warm coat or a hot (i.e., warming) drink. It also seems much less used than 温 for metaphorical warmth (warm-heartedness etc), just as a cold-hearted person would be described as tsumetai, not samui.

While the two are not absolutely distinguished, if you bear in mind their general tendencies it will help you to use them in a natural-sounding way (for your own use you can treat them as equivalent to samui and tsumetai on the warm end of the scale) and to catch the nuance when you see them used.

Note that both forms of atata(kai) are used to make the two verbs atatamaru and atatameru. This is a regular maru-meru transitivity pair, so if you know the Honorary Fourth Law of Japanese Transitivity, you will know exactly what the words mean!