A friend wrote:

A friend wrote:

I really wish we could learn Japanese kanji in the light of symbolism and deeper meanings in Asian language schools. The idea that Chinese ideograms are evolved forms of merely primitive drawings never made complete sense for me, specially in the face of such “abstract” words.

I think that is a very good approach, and one that not only makes learning Japanese kanji a lot more intuitive, but also deepens our minds in more fundamental ways. We should begin though, by looking at the underlying philosophy of language in general and Japanese kanji in particular.

It is very difficult to learn Japanese kanji if one has no idea of why they mean what they mean — if they are seen as merely arbitrary symbols, or if the symbolism is considered erratic and “primitive” rather than logical and clear.

It is said that the Chinese ideograms that form the basis of Japanese kanji evolved from primitive drawings. Is that true?

Yes, of course it is. The problem here lies in what we mean by the word “primitive” and in realizing that modern language has been fundamentally altered by the “progressist” ideology. In earlier English, as in Japanese and other languages, the concept “primitive” had a positive implication. It implied: earlier = purer, wiser. In modern language it implies: earlier = cruder, less intelligent. This is the fundamental basis of recent “historical” thinking.

This will influence our view of Japanese kanji/Chinese hanzi as it will of everything else. And more immediately, it will make it a lot harder to learn Japanese kanji.

So are “primitive ideograms” closer to the grunts of apes than our own language? Or are they closer to the Ideas of the Angels: purer, simpler and far more profound – and more immediately related to the fundamental Divine Ideas or Essences that are the Source of all manifest existence?

All people have believed the second of these things until historically very recently. In the 16th century in Western Europe the idea of primitive = crude; newer = better was just emerging. Most people still held the traditional view. By the late 19th century it had become near-universal in Western Europe and was being spread by economic and military force to the rest of the world.

The Déanic science of language is based on the traditional view, as stated in the Gospel of Our Mother God:

What is your language of the earth, My children? What are the words of thy speech? Are they not fallen from the first, the mother language?

Japanese kanji/Chinese hanzi are in their origin visual representations of the fundamental Ideas behind words. They certainly “evolved” over time, as all things evolve. Evolution meaning “unrolling” and being essentially a mirror of the process of manifestation itself – that is, increasing deployment on the substantial or horizontal level and continual weakening of the Essential or vertical dimension.

Evolution of language is necessary as we 1) need to make things more horizontally complex and as 2) the simple hints at underlying truth (and all language can only hint at the inexpressible) need to be expanded and made more explicit, and also as material needs multiply and language has to take on more and more material tasks. These should be understood as the two aspects of the evolution of language.

Both are “outward” unrollings (e-volutions), but one is directed toward maintaining contact with the Center in a more dispersed environment and the other is directed toward greater interaction with the periphery, that becomes necessitated by increased “materialization” or outward manifestation.

Ideally, these two dimensions of evolution should take place together and in balance. Where the first of them (which should always be the subordinate, because Wisdom should precede and guide Method) becomes dominant, an unbalance is created, and ultimately the entire foundation of language can become lost, so that “primitive language” is regarded as inferior to “developed language” – which is like believing that the sun is the crude ancestor of the sun’s reflection in a puddle*.

Partly from the natural attrition of the historical cycle – but very largely under Western influence (I suspect there were in the early 20th century, and maybe still are, daisensei who are very aware of the metaphysics of Japanese kanji/Chinese hanzi, but the Western pop-Darwinist approach has become the “official” view) the understanding of the symbolic depth of the characters has become obscure to the majority.

When we look at Japanese kanji, therefore, we attempt to see them in the light of fundamental symbolism and may bring into play all that we know of it. We should also bear in mind that the “evolved” forms of the characters should, on the whole, be regarded as legitimate since they were developed over centuries by minds that were very far from being symbolically blind, as the modern West Tellurian mind is. Of course, we would make an exception in the case of “official reforms” made by bodies influenced by Western ideology, such as Simplified Chinese.

We may look at Japanese kanji/Chinese hanzi, then, as images that express the universal language of symbolism, which has its roots in the nature of being. This language makes continual use of such fundamentals as the Center, the Axis, the Heart, the Sun, the Moon, the Vehicle (chariot), the Mouth, the Hand, and so forth. These are among the fundamental metaphors of speech, thought and being. Such a language is highly suited to a culture that has expressed itself in Ch’an/Zen and Taoism, and is more prone to approach the Absolute through aids to direct apprehension than through attempts to capture It in highly-concretized doctrinal formulations.

It is perhaps even a little outside the spirit of such a tradition to suppose that there is a single “key” to a kanji character, and since the symbolism opens out onto the universal, containing all possible perspectives, there is not. At the same time, the Sun is always the Sun and the Heart always the heart, and so forth, so we are legitimately able to examine the characters in the light of the universal language of symbolism and provide some hints toward their elucidation which should help us not only to learn Japanese kanji but also to have a deeper understanding of the roots of human thought and existence itself.

* For, after all, the sun does not even touch our puddle, far less ripple with it, or shatter when a horse steps in it. The sun is out of touch with reality and lost in crude, ancient myths of a sky beyond the puddle. Luckily we have now evolved a much more sophisticated and realistic puddle-language.

Avidyapedia

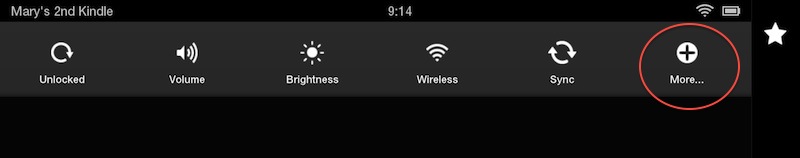

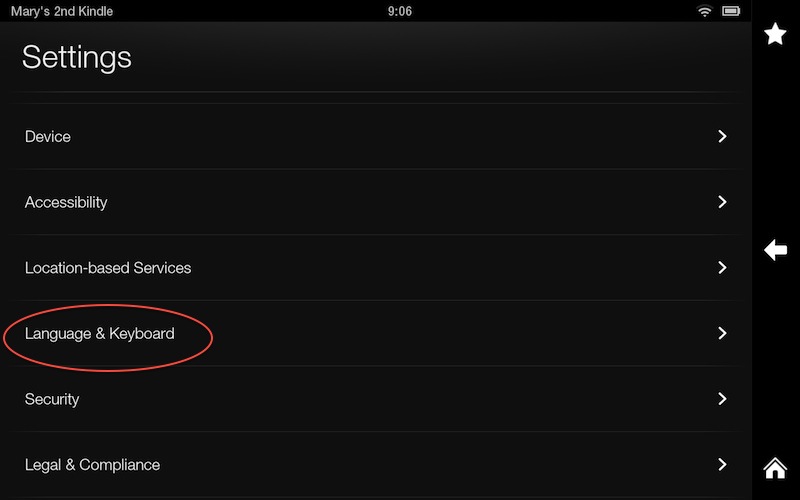

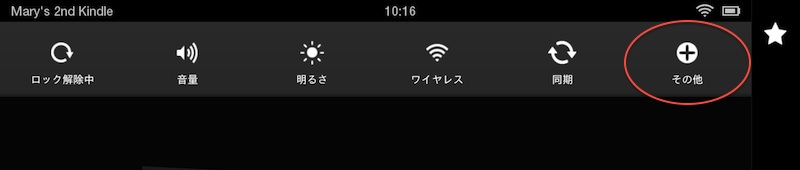

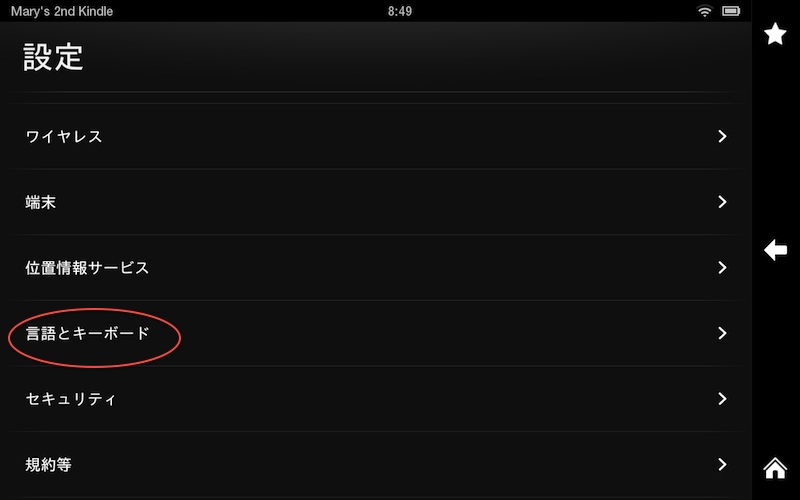

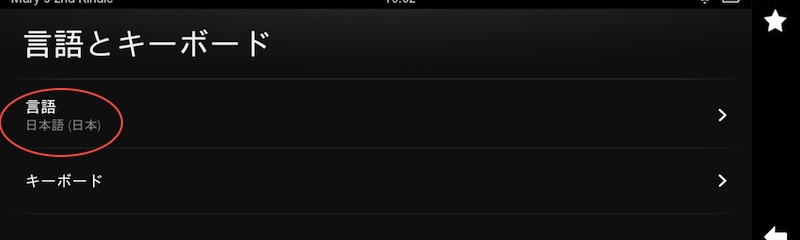

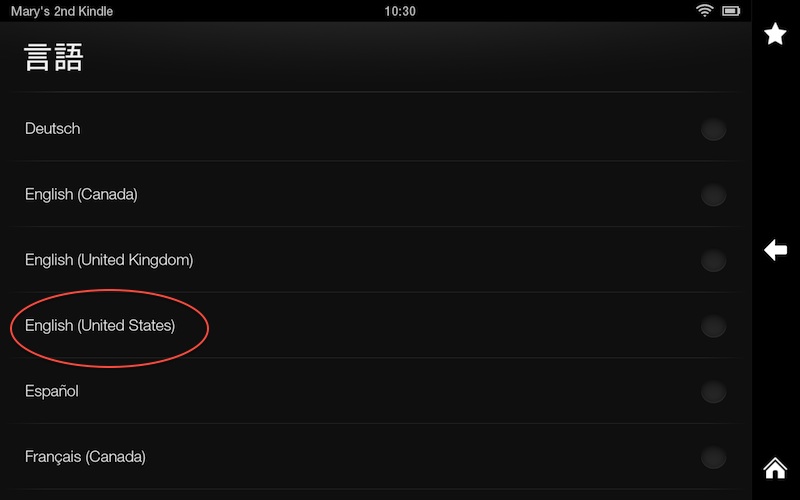

1. First of all, do make sure you have the Rikaichan lookupbar installed. You’ll find it under “Tools” in the Firefox menu. Hee – yes, my pasokon is in Japanese, but you’ll find it under the Tools (ツール) menu, right between Bookmarks (ブックマーク) and Windows (ウインドウ). Select Rikaichan Lookupbar so it gets a check-mark next to it and the toolbar will appear beneath the browser’s address bar. 2. This toolbar has important uses which we will discuss elsewhere, but right now what you need is this cogwheel icon:

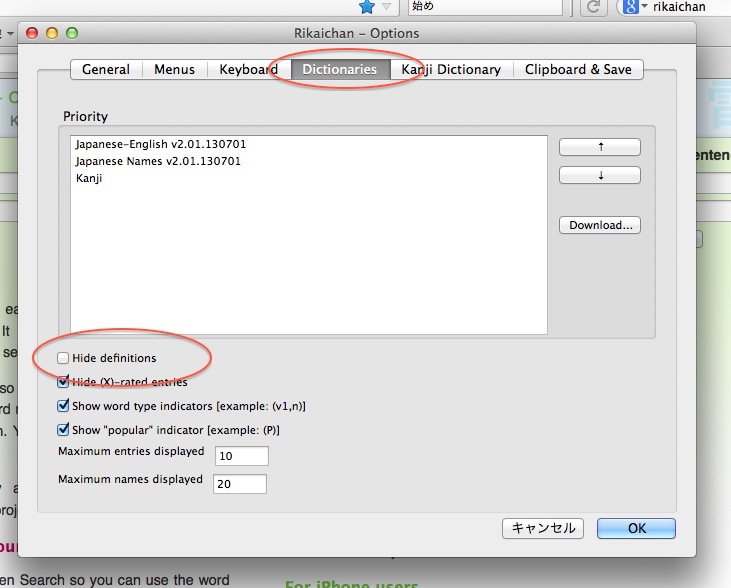

1. First of all, do make sure you have the Rikaichan lookupbar installed. You’ll find it under “Tools” in the Firefox menu. Hee – yes, my pasokon is in Japanese, but you’ll find it under the Tools (ツール) menu, right between Bookmarks (ブックマーク) and Windows (ウインドウ). Select Rikaichan Lookupbar so it gets a check-mark next to it and the toolbar will appear beneath the browser’s address bar. 2. This toolbar has important uses which we will discuss elsewhere, but right now what you need is this cogwheel icon: The second ringed area shows where the problem lies and why Rikaichan doesn’t show definitions. You can hide X-rated entries, which obviously you will, since we kawaii girls don’t want our kirei pasokon made all kitanai with foul-mouthed stuff. But you can also hide definitions, which if you are advanced you may want to do. So if you want definitions you must make sure “Hide definitions” is unchecked. “But Tadashiku!” you expostulate (isn’t expostulate a good word?) “Hide definitions IS unchecked and still Rikaichan isn’t showing definitions. What do I do now?” Well, this is a funny little bug that crops up in Rikaichan from time to time. It thinks “Hide definitions” is checked even when it isn’t. Fortunately the fix is very simple. You have to do a very unintuitive thing and check “Hide definitions”. That’s right. Go ahead and tell Rikaichan you want the definitions hidden. Then close the preference window. Hover over some Kanji and make the pop-up box come up – complete with no definitions. Now go back to the cogwheel and open the Options window again. Uncheck “Hide definitions”. Close the Options window and voila! You Rikaichan is showing definitions like a good Rikaichan again. It’s easy when you know how! So next time Rikaichan doesn’t show definitions, you know what to do. Remember you saw it at Kawaii japanese! Did this solve your problem? Let us know in the Comments below.

The second ringed area shows where the problem lies and why Rikaichan doesn’t show definitions. You can hide X-rated entries, which obviously you will, since we kawaii girls don’t want our kirei pasokon made all kitanai with foul-mouthed stuff. But you can also hide definitions, which if you are advanced you may want to do. So if you want definitions you must make sure “Hide definitions” is unchecked. “But Tadashiku!” you expostulate (isn’t expostulate a good word?) “Hide definitions IS unchecked and still Rikaichan isn’t showing definitions. What do I do now?” Well, this is a funny little bug that crops up in Rikaichan from time to time. It thinks “Hide definitions” is checked even when it isn’t. Fortunately the fix is very simple. You have to do a very unintuitive thing and check “Hide definitions”. That’s right. Go ahead and tell Rikaichan you want the definitions hidden. Then close the preference window. Hover over some Kanji and make the pop-up box come up – complete with no definitions. Now go back to the cogwheel and open the Options window again. Uncheck “Hide definitions”. Close the Options window and voila! You Rikaichan is showing definitions like a good Rikaichan again. It’s easy when you know how! So next time Rikaichan doesn’t show definitions, you know what to do. Remember you saw it at Kawaii japanese! Did this solve your problem? Let us know in the Comments below.