Youkai Watch is a huge phenomenon in Japan. The game Youkai Watch 2 has sold over five million copies and it hasn’t been released outside Japan. You see Youkai Watch everywhere, from cereal packs to facecloths.

Youkai Watch is a huge phenomenon in Japan. The game Youkai Watch 2 has sold over five million copies and it hasn’t been released outside Japan. You see Youkai Watch everywhere, from cereal packs to facecloths.

The Youkai Watch phenomenon resembles Pokemon in its heyday, and indeed it is in many ways very similar in concept to Pokemon.

As I write, the first game will go on sale in America next week (styled Yo-kai Watch). As it happens (the two events aren’t connected) I have just begun playing it (in Japanese, of course). Whether it will be anything like as big in America as it is in Japan remains to be seen. Will it be the next Pokemon in the West too? Or some obscure Japanese thing that never really caught on? People said Pokemon was “too Japanese” for the West, but Yo-kai Watch is considerably more “Japanese” than Pokemon.

Youkai Watch for the Japanese Learner

The question that concerns us is: Is Youkai Watch a good game for the Japanese learner?

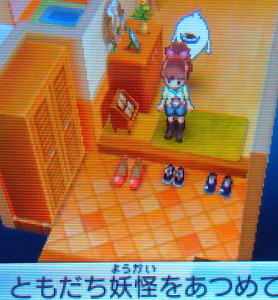

I would definitely say that it is. To begin with it has full furigana. Even Pokemon X/Y forces you to choose between all-kana text and text with kanji and no furigana. Personally I found all-kana even harder to read than than furigana-less kanji. Fortunately Youkai Watch doesn’t make one choose the lesser of two evils.

The game is packed with text at a level that is good for not-too-advanced learners. Even NPCs have a lot to say, and what they say is generally less random and odd than in Pokemon, which gives the player a much better chance of understanding what they mean.

But Youkai Watch also has a “secret ingredient” that I think makes it a winner for the Japanese learner.

I am guessing that most Japanese learners, especially those who are self-learning rather than doing it for school, have a love of Japan too. This is where Youkai Watch really shines. The game’s beautifully crafted 3D world is a kind of Japan simulator.

Youkai Watch will inevitably be compared to Pokemon. It is essentially the same monster-collecting/battling premise wrapped in a similar RPG environment with a similarly heartwarming underlying story.

The main difference is that while Pokemon is set in an alternate world where everyone interacts with Pokemon, Youkai Watch is set in the current Japan that its players know and love. Youkai are invisible to most people, just as they are in real life.

If you have spent time in Japan not doing “tourist things” but just wandering around a small town observing and drinking in every little thing, then Youkai Watch is going to bring a sense of heart-wrenchingly natsukashii deja vu.

Your house has a real genkan, just like the house you lived in in Japan. When you leave you will automatically put your shoes on. When you re-enter you will automatically take them off and leave them there. Even the lavatory is detailed enough that you can see it is a Japanese-style one with an integrated handbasin and cistern.

When you leave the house you find that you are wandering Japanese streets just as you do/did in Japan. The shop fronts, the cars, the pedestrian crossings with bicycle lanes (you press the button and wait in the same way). The konbini – just like the real ones, the last shelves before the checkout have ready-to-eat food. When you buy some, you almost expect them to offer to warm it for you in the denshirenji the way they do in real life. The schools, the parks, the rainy days with ubiquitous umbrellas. Every little detail is so very much Japan.

If you have never been and want to get the feel of Japan, this game (the Japanese version, of course) is ideal. I imagine you will have the reverse reaction when you do get there. “Oh, this is just like the game!”

The makers of Youkai Watch, Level 5, also made Fantasy Life, and if you play both, you will realize how many things have been taken from that game. Not just its excellent 3D-world infrastructure, but also its ability to lead you around the game. If you want it, the game will constantly tell you your next objective and place pointers on the bottom screen map to lead you there.

You can turn this off in the options if you don’t like it. Personally I am 方向音痴 and get lost in games as easily as in real life, so I really appreciate this. Also, as a Japanese learner, you very likely want to spend as much time as possible with the extensive text rather than trying to figure out where you need to go next and how to get there.

On the other hand, if you are anything like me you will wander around quite a lot, just as I do in physical Japan. There is so much to drink in. You will want to read the shop signs and the posters in the bank and get annoyed when some of them aren’t quite detailed enough. If there is one thing I would add to this game it is a zoom function, but then I guess most people aren’t otaku-ing about the depth of Japanese detail. The amazing thing is that there really is enough everyday detail in the game to otaku about. And the fact that it is all in glorious glasses-free 3D is the frosting on the cake!

Fortunately, the game also rewards your wanderings. There are things to find everywhere: under cars, in tiny back alleys, up trees, and even under the ubiquitous (and functional) vending machines.

Like Fantasy Life before it, Youkai Watch is a generous game packed with surprises and extras that you didn’t expect. There is always something new and rich waiting for you at every turn. Rather than being a second-rate imitation of Pokemon, it brings many, many new things to the formula, refreshing and invigorating it. I am not saying that Pokemon is tired. I don’t think it is, even now. But Pokemon-alikes always were.

Youkai Watch is fresh, innovative and delightful, and it deserves every bit of the huge success it is enjoying.

[review_bank review_id=1]