The idea of learning to think in Japanese—actually switching one’s “inner monologue” from English to Japanese—is one I have been thinking about and working with for some time.

The idea of learning to think in Japanese—actually switching one’s “inner monologue” from English to Japanese—is one I have been thinking about and working with for some time.

I have read advice on this, which essentially boils down to making yourself say the things you normally say to yourself in Japanese. Like “what a nice day”, or “where did I put that pencil?”

Eventually, because the mind is a creature of habit, Japanese will begin to dethrone English as your default means of thinking.

That is the theory and, given a lot of determination, I think it works. But it is possible to make the process much easier and more effective.

Let us just think things a little further and wonder to what extent does one actually have an inner monologue? In English or Japanese?

Having an inner monologue to a large extent rests on being alone. If you are in company you say what you think to those you are with. If you are alone you say it to yourself. Maybe.

We all work differently, so I can only talk about my own experience. I am an extravert and a person to whom communication is a paramount need, even though circumstances lead me to mostly live the life of a hikikomori (sometimes it is hard being a doll in a human world).

My word-world revolves around communication. When I think things in words it is usually because I am thinking in terms of communicating them. Otherwise I tend to think in a vague non-verbal kind of way.

Now when I say “thinking in terms of communicating them” I don’t mean that I am necessarily going to communicate them. Often I am not. But I am thinking them in words with a view to their potential communication. What I might have said if such-a-person was there. How I might tell the story. How I might blog it. If I used Facebook, I would probably think what I might post there. Etc.

You might state things in a somewhat witty or sardonic manner. You are not trying to amuse yourself. You are saying what you might say to amuse someone in your circle if they were present.

Now you may not be the same. I don’t know how other people are. But in my experience “inner monologue” insofar as it is really “monologue” (i.e. verbal) at all is actually potential outer dialogue.

In practice—at least if you are anything like me—this has important effect on how (and whether) we can change our thinking to Japanese.

When I am thinking about writing or talking, to a person or an audience, in English, I think in English. When I am thinking about writing or talking, to a person or an audience, in Japanese, I think in Japanese. It really is as simple as that.

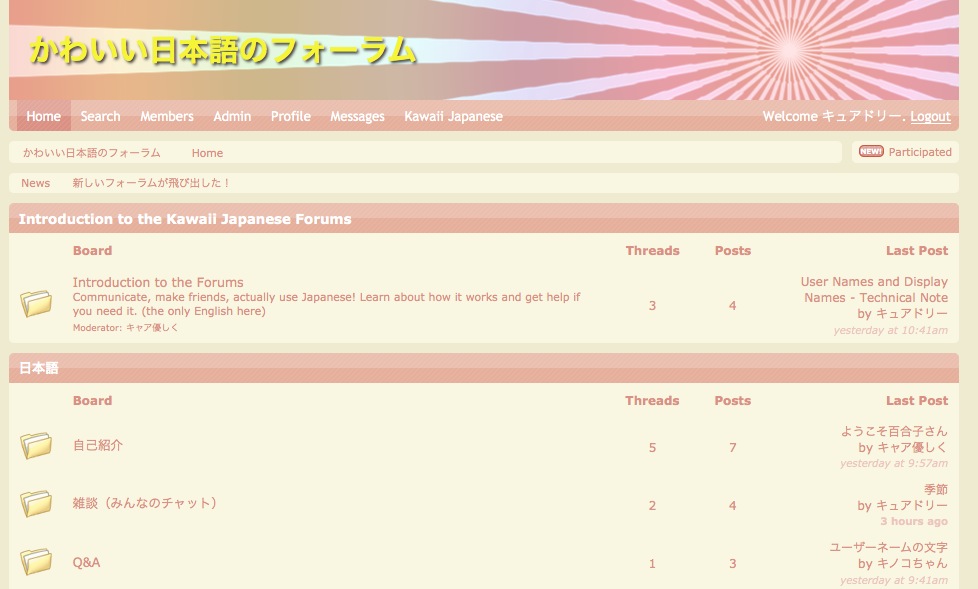

The “brute force” method of making myself say things to myself in Japanese is really doing it the hard way, and it only lasts as long as I am actually thinking about it. But if I think in terms of expressing it, say, on the Kawaii Japanese Forums, or to someone with whom I habitually communicate in Japanese, it comes out in Japanese naturally.

Language is made for communication, and communication (at least in my case) determines our language. Even in English, we will think differently, make different kinds of joke, be more or less formal, depending on what kind of person we are (vaguely) thinking of speaking to when we verbalize to ourselves.

Mentioning the Kawaii Japanese Forums sounds a little like self-advertisement, but it isn’t as if we make any money out of them, and no one else seems to be doing anything similar. They absolutely aren’t the only way of doing this, and it is good if you have various people that you regularly speak to/correspond with in Japanese only. In my experience that only is important because it determines Japanese as the pure default language in that relationship. When I think about A-san I think in Japanese.

Set up as many such situations as possible. Then when you find your inner monologue is in the wrong language, instead of thinking “I must think in Japanese”, just think of speaking to A-san about whatever you are thinking, or posting it on the Forum (even if it is something you might not actually post). If you have Japanese-only Twitter, think about tweeting it. Or do. (I don’t tweet a lot myself, but if you tweet at me in Japanese, I’ll tweet back). But you don’t have to do it. You just need to gear your mind into that communication-sphere, which is Japanese.

But for that, of course you must establish Japanese communication-spheres. And keep them regularly active. If you don’t know where to start with that, I really do recommend popping along to the Kawaii Japanese Forums. And join in! Really, we welcome newcomers of every level, and we are all learning, so don’t feel shy. えんりょしないで!

Language is communication. Communication is people. Inner monologue is outer dialogue internalized. Thus (certainly in my case and very possibly in yours) the key to inner monologue is outer dialogue.

I recently discovered the Funnel Theory of language learning.

I recently discovered the Funnel Theory of language learning.