Disclaimer. This article is not about typing Japanese, although I have discussed that earlier.

It is about the organic way of learning Japanese and what we can discover about it by noticing how we touch-type.

I actually started out by replying to a comment on my typing article. But I found there was so much to say, and I think it is so important, that I made an article about it.

Cure Yasashiku said:

As an interesting aside, with just one finger disabled, I was not able to touch type at all…even with the OTHER hand…it was really strange.

Now I do not find this strange at all. In fact I would have been very surprised if it hadn’t happened.

Why?

Because touch-typing, like language but on a much smaller scale, is an organic skill. That is why it can teach us so much about language.

The reason Cure Yasashiku could not touch-type with one finger disabled is that touch-typing is a complete, organic whole. You can’t half-touch-type. You are either touch-typing or you aren’t. And for that you need all your fingers (if one finger was permanently disabled you might find a workaround, but that just means adopting a different style of touch-typing).

When you are touch-typing the process is automatic, like speaking your native language or a language you have really learned. You aren’t thinking “what key is where?” In learning language, we are aiming for the same automaticity, rather than merely theoretical knowledge of grammar, kanji and vocabulary.

Using Japanese immersively is like touch-typing. Treating Japanese as a “subject of study”, with the occasional “practice” conversation or reading, is hunt-and-peck.

With hunt-and-peck we never get away from using our eyes to fully trusting finger-memory. With “study-Japanese” we never get away from using English as our base-language and continually relating Japanese to it.

Once we are fully touch-typing we forget what key is where. Our fingers go straight to it automatically, but if you ask “where is the ‘m’ key?” I don’t even know.

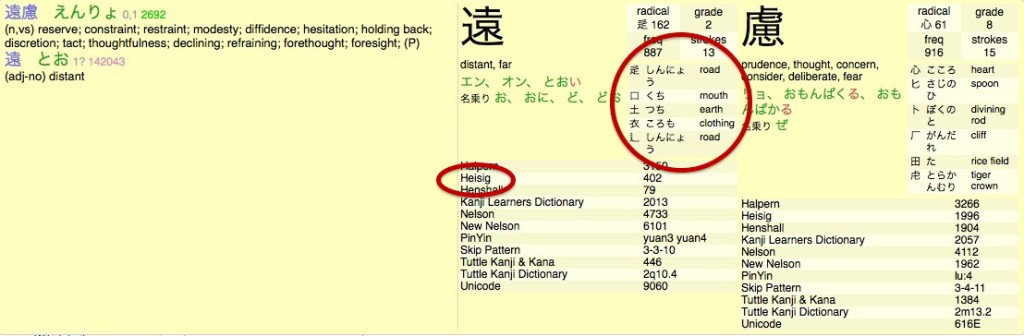

Once we are fully immersed in Japanese we are no longer “peeking” by thinking “what is this word in English?” We are treating the Japanese word as its own reality: an organic part of the entire Japanese “keyboard”. Sometimes we will not even remember how to put a Japanese word into English (some are very hard to express in English anyway).

Many Japanese learners never get away from hunt-and-peck Japanese. They may pass exams, just as hunt-and-peck typists can become pretty fast. But they never really internalize Japanese to the point where it lives in their hearts as a whole system unrelated to English.

These people populate “Japanese learning” forums, avidly discussing Japanese day after day – in English. And the interesting thing is that a very significant minority of these people are not native English speakers.

What does this mean? I have talked about English speakers regarding English as “Real Language” and Japanese as just “a language”. But in fact non-English speakers often do the same.

Why?

Because they need English. If they want to participate in large Internet forums, if they want to immerse themselves in the dominant popular culture of this world (can’t think why anyone would, but people do), If they want to discuss Japanese (or many other things) with any significant number of enthusiasts, they have to use English.

Thus English is not just a “subject of study” to them. English becomes real language in which an actual part of their life and real communication takes place.

To use our typing analogy, with English they have switched from hunt-and-peck to touch-typing. But, unless they are living in Japan (and not always then) Japanese does not apply the same pressure. They don’t need it. It can remain a “subject of study”. It can continue to be hunt-and-peck Japanese.

When I was in Japan, I spent a very short time (less than a week before I fled back to the Mie-prefecture countryside) in a shared house for foreigners in Tokyo.

One of the first people I met there was a French student, who was studying at a Japanese university. Before he even saw me (I was on the other side of a half-open door) he greeted me in English.

I do not speak English in Japan, so I replied with a hesitant “Sumimasen…”

The door was open by now and the Frenchman stared at me.

“Nihonjin desu ka? Iie…” (Are you Japanese? No, you’re not…)

He was clearly shocked and surprised. He seemed to look over my shoulder in case four horsemen were about. Here was a European-ish looking foreigner in Japan speaking Japanese. Why on earth would that happen? Even if I was a Finn or a Russian, surely I could summon up some English.

However, when it became clear that I didn’t speak English, we continued quite happily in Japanese. We spoke on several occasions afterward and always in Japanese. But under “normal circumstances” every word we said to each other would have been English, even though we were in Japan and both perfectly capable of communicating in Japanese.

We communicated in Japanese because we had to. There wasn’t another language that both of us were able/willing to talk.

All my discretionary activities are in Japanese. If I can’t read a novel in Japanese, I can’t read it. If I can’t play a game in Japanese, I can’t play it. Some people have said “that’s real dedication”. Now if by dedication they mean “exceptional self-sacrifice” or something like that, I wouldn’t agree at all.

But if they mean that part of my mind is a “dedicated device” that only uses Japanese then yes. That is exactly the point. I do not regard English as the language of default. I regard Japanese as the language of default.

I am not living in English and peeking at the Japanese keys through English-language eyes. I am living in Japanese and touch-typing.

When we first learn to touch-type it is slow and laborious. We do it in class and go back to hunt-and-peck the minute we have to type a real essay or email. But at some point we have to make the switch and use touch-typing as our real input method. Otherwise there is no point learning at all.

It is the same with Japanese, at least if we are serious enough about it to want to make it our own language. At some point we have to stop hunting-and-pecking through the eyes of English and start touch-typing in pure Japanese.

And the earlier we start doing that, the better. It doesn’t matter if it is slow at first. What matters is that we are really living Japanese if only in a tiny way.

A lot of Japanese learners – even quite advanced ones – never make this transition. But it is possible to start doing it as soon as you have learned basic grammar.

I hope you will.