If we look at kanji in the light of traditional philosophy, they make a lot more sense. In kanji symbolism, fire and movement, life and humanity are depicted in terms of the ancient metaphysical thinking common to all traditional civilizations.

King Lear was in line with tradition when he called humanity a “forked animal”. This is exactly what the kanji for a person 人 (hito on its own, jin/nin in combination) shows. Notice that the “fork” is all it shows. there are no arms or head. Just, as Shakespeare said, the forked animal.

Kanji reduce things to the essential. Why is the fork the essential feature of humanity? Humanity is, in traditional thought, the center of the Middle Kingdom – the creature that links earth and heaven. The being that stands at the Axis of the World. Humanity is upright and stands on two legs rather than four.

Being “between earth and heaven” humanity is inherently dual. We have both a Heavenly and an earthly nature. Or to put it in Buddhist terms we have both a samsaric nature and a Buddha-nature. And we are always choosing between the two. That is how we create our karma.

So the fork 人expresses what is essential to humanity.

Of course people do have arms. When they hold them out wide they are saying something is this big. So we get 大 big.

Humanity also has within it the Divine Fire, the spark of life. So when we want to depict fire, we think of it in this most fundamental sense – as the Solar principle on earth. All fire comes from the Sun in traditional thought. Wood burns because it was fed for years on the warmth and light of the sun. When wood is burned, it releases that warmth and light in the form of fire.

But the highest fire – the earthly avatar of the Heavenly Sun – is the Solar principle in each human being – the Divine Spark – 火. Thus the kanji symbol fire (ka) shows the human being and the divine flames. Why two? Because we can use that heavenly power for good or evil, so even the fire in us is expressed in two flames, continuing to express our “forked” duality.

The first non-human-powered vehicle was the chariot, and, as we would expect, the chariot is deeply rooted in traditional symbolism. In the Bhagavad Gita, the entire teaching of the Scripture is given while Krishna and Arjuna are in the chariot. The chariot is the world, or human body, and within it are the Divine Principle (Krishna) and the human principle (Arjuna).

The design of the chariot itself reflects this. The body of the vehicle is the world, or the human body (these two “vehicles of manifestation” are called the macrocosm and the microcosm – the great world and the little world – in traditional Western thought). Through its center passes the World Axis with the two wheels as the dual principles that lie “above” and “below” the world.

The world itself is often described as a “field” (kshatra in Sanskrit). The chessboard is called kshatra because it represents the world in its black/white duality – the field on which the conflict of light and darkness takes place.

In kanji the field looks like this: 田. This is the simplest possible form of the symbolism that is elaborated on a chessboard or a go-board. The fourfold division is that of the material world – its four directions, four elements, four seasons.

Add the World Axis (axle) and the upper and lower wheels, and we have the chariot: 車.

The chariot being the first and fundamental human vehicle, 車 is used in Japanese for every kind of wheeled vehicle. The basic vehicle today is the car, so 車 kuruma means just that. Interestingly our English word “car” also originally means “chariot”

The Etymological dictionary tells us:

Car: “Wheeled vehicle,” from Anglo-French carre, Old North French carre, from Vulgar Latin *carra, related to Latin carrum, carrus (plural carra), originally “two-wheeled Celtic war chariot”.

Kanji etymology and English etymology alike preserve the identity of the modern “fundamental vehicle” with the essential Archetype of the Chariot.

From this basic chariot/car, which is pronounced kuruma, we have many combinations (in which it is pronounced sha. So we have, for example, 電車 densha – or electric-vehicle – a train and 自転車 jitensha, a self-revolving vehicle or bicycle (note that the 自 ji of jitensha always means oneself, as in 自己紹介 jikoshoukai, self-introduction, or 自己中 jikochuu, self-centeredness. So self-revolving means “revolved by oneself”, not “revolving itself”.

Now if a vehicle has to carry a heavy weight, we may need to add extra wheels. For carrying heavy loads the four-wheeled cart was used. Thus the concept heavy is represented by a four-wheeled vehicle. 重い omoi, heavy.

As in English, and most other languages, the concept of heavy may also be used metaphorically to mean “important”. We talk about “the gravity of the situation” or “a weighty matter”. In combinations 重 is pronounced juu, so we get, for example, 重点 juuten, “important point” (literally heavy point).

力 riki is strength or power. We will see is in many, many combinations. If you apply strength to something heavy, you move it. Thus 動く ugoku means “to move”.

動 in combinations is pronounced dou. So, for example, we get 動物 doubutsu, meaning animal. The kanji literally means move-thing. So we can see that the Japanese word for animal is essentially the same as the Latin/English word “animal” – something animated or moving.

We will see all these elements in many different combinations. For example we can tie together many of the things we have learned today with the word 人力車 jinrikisha, shortened in English to “rikshaw”.

I am sure you can see that the word literally means “person-powered vehicle”.

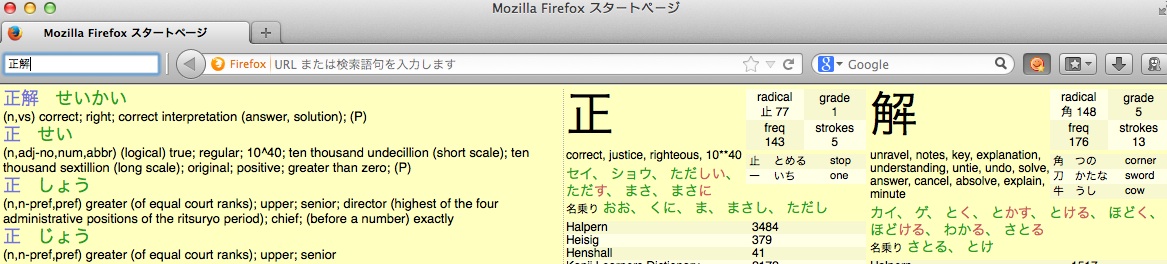

2018 UPDATE: Rikaichamp does not have the search box, but you can get this window by pressing return while the regular pop-up window is active.

2018 UPDATE: Rikaichamp does not have the search box, but you can get this window by pressing return while the regular pop-up window is active.