“There are no hard-and-fast rules to Japanese transitive and intransitive verbs. You just have to learn them on a case-by-case basis”. This is the conventional wisdom on the subject. Another huge bunch of random facts that you “just have to learn”.

“There are no hard-and-fast rules to Japanese transitive and intransitive verbs. You just have to learn them on a case-by-case basis”. This is the conventional wisdom on the subject. Another huge bunch of random facts that you “just have to learn”.

We got rid of most of the “random facts” in grammar by showing how logically the whole language fits together in Unlocking Japanese. An evening with that little book gives you a shortcut through the thickets that take most learners years to master, just by showing how Japanese really works.

Can we do the same with transitivity pairs? To a large extent we can. There are a lot of Google searches for “Japanese transitive and intransitive verb worksheets”. Worksheets! You don’t need worksheets, for heaven’s sake! You need some good information!

So let’s get started!

Video version

Transitive and intransitive verbs – what they are

We’ll start off by looking very quickly at what transitive and intransitive verbs are, because some people get confused and mix up intransitive with the so-called “passive” (it isn’t really passive).

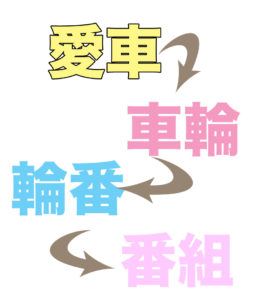

As is often the case, the Japanese terms for transitive and intransitive are much clearer – and more accurate – than the English ones. The word for “verb” is 動詞 doushi, which means literally “move word”. A word for an action. And the words for transitive and intransitive verbs are

自動詞 jidoushi – self-move word (“intransitive”)

他動詞 tadoushi – other-move word “(transitive”)

In English “dance” is an intransitive verb because it is a self-move word. We say “I danced”. We can’t say “I danced Jane”. It describes self-movement, not a movement done to someone or something else.

“Throw” is a transitive verb. We can say “I threw a ball”, but we can’t just say “I threw”. It is an other-move verb and has to have an object.

“Eat” and “sing” can be transitive or intransitive. I can “eat bread” or I can just “eat”. I can “sing a song” or I can just “sing”.

In Japanese we sometimes use a different form of the verb for the transitive and the intransitive (the other-move and the self-move) version of the action.

But by no means always. The examples given above, “eat” and “sing”, work just the same in Japanese as in English. The transitive and intransitive forms are the same.

But there are various pairs like

負けるmakeru – “lose”

and

負かすmakasu – “defeat” (lit. “cause-to-lose”)

where the transitive and intransitive forms are different. And as you can see, rather than being an unnecessary bother they are often a gift. English learners have to learn “lose” and “defeat” as two quite separate words. In Japanese, if you understand makeru, you can understand makasu. Especially when you understand the simple rule that makes one clearly transitive. The rule that I call “the First Law of Japanese transitivity”.

So let’s go right ahead and meet the Three Laws.

The Three Laws of Japanese transitive/intransitive verbs

Aru and suru are the two most basic verbs in Japanese. As you know, they mean “be” and “do” respectively.

Their sounds are used in many ways to indicate that a verb is closer to the “being” or the “doing” end of the scale.

For example, the so-called “passive conjugation” ends with the helper-verb reru/rareru, which has its roots in aru, while the causative ends with the helper-verb seru/saseru, which has its roots in suru.

Learn the simple truth behind Japanese so-called “conjugation”.

Can you guess which side of the scale transitive and intransitive (other-move and self-move) verbs respectively fall on?

Yep. You guessed right. So you shouldn’t be too surprised to learn that the First Law of Japanese Transitivity is:

All verbs ending in すsu are transitive verbs. Whether they have an intransitive “pair” or not.

Su-ending verbs are based in suru. They are transitive.

The eru→asu transformation seen above in makeru→makasu is a very common pattern which you already know from

出るderu – “come out”→ 出すdasu – “take out”

There are other patterns such as

落ちるochiru – “fall” 落とすotosu – “drop”

Some are a bit irregular, but that doesn’t matter because all you need to know is that if it ends in す it’s transitive.

Here is the Second Law:

Verbs ending in aru are intransitive

As you would expect! Aru-ending verbs are based in aru – “be”. This means not just ある-ending words, but words ending with any kana in the あ-row + る.

The most regular pattern here is aru→eru

上がるagaru – “rise” → 上げるageru – “raise”

下がるsagaru – “descend” → 下げるsageru – “cause to descend”

重なるkasanaru – “lie stacked or piled” → 重ねるkasaneru – “(to) stack or pile”

There are many, many pairs that conform to this pattern. A few have a different pattern, such as

包むkurumu – “wrap” → 包まるkurumaru – “be wrapped”

Again, it doesn’t matter because all you need to know is that if a version ends in aru, it is intransitive.

The Third Law of Japanese Transitivity is:

-u→-eru flips transitivity

As we know, so-called “conjugations” (actually helper-verbs) that end in る usually change a the resulting compound-word from whatever it was before into an ichidan verb (sometimes called a ru-verb) – the most basic type of verb – with an altered meaning.

This also happens when we flip transitive and intransitive verbs with u→eru. Whatever ending the verb originally had, its final character becomes the え-row equivalent and る is added.

Learn the simple Japanese core fact of kana-row transformation that the textbooks don’t teach.

It is now an ichidan (ru) verb meaning the opposite (in transitivity terms) of what the original verb meant.

The problem here is that (unlike the aru→eru pattern of the Second Law) this u→eru ending can flip transitivity either way. So we don’t immediately know which half of a transitivity pair the –eru version is.

However, there are some tricks that can help us.

Untangling the other Japanese transitivity pairs

There are a few sub-rules that make the “others” much easier.

〜む-mu → 〜める-meru flipped pairs – The honorary 4th Law

The 〜める-meru version is always the transitive verb

There are a lot of these mu→meru pairs. So many that we can almost regard this as an honorary Fourth Law.

I recommend having one example in your mind as a reference-point, such as

痛むitamu – “hurt” (be in pain) 痛めるitameru – “hurt” (cause pain)

The same is true for bu→beru and tsu→teru. The –eru (flipped) version is always transitive. Remember that b is sometimes interchangeable with m in Japanese (as in sabishii/samishii) so they often work in the same way. Unlike mu→meru, there aren’t a large number of these two.

〜せる-seru versions are always transitive

Some pairs have a 〜せる-seru-ending version, such as

乗るnoru – “get onto, ride on” → 乗せるnoseru – “put onto”

This せるseru is a close relation of するsuru and always marks the transitive verb.

This actually covers most of the possible endings. What we are left with is

く、ぐ ku, gu → ける、げる keru, geru

うu → えるeru

and る-ru-ending verbs that don’t fit either of the first two Laws.

For these, unfortunately, there are no general rules. They can flip either way. And there are quite a few of them. So the “gotta learn ’em all” school might seem to be around 20% right.

But wait. There is more we can do. We can apply the Basic Concept “rule”.

The Basic Concept “rule” for Japanese Transitivity pairs

For those transitivity pairs that don’t fit any of the above rules, we can use the Basic Concept “rule”, which is less hard-and-fast but actually quite intuitive as you become more familiar with Japanese by immersion.

Remember that –eru flips a verb from intransitive to transitive or vice versa. In other words, one of the two is the “base verb” and the other is the “flipped version”. If you remember that the extended -eru (え-row plus る) is actually a helper-verb it becomes much more intuitive.

Let’s take some examples:

売るuru – “sell” → 売れるureru – “be sold” (sell as in “sell like hot cakes”)

It is pretty clear here that the base concept is the act of selling (transitive) and that being-sold (intransitive) is the extended or “eru-flipped” version.

Conversely, with:

従うshitagau – “obey, follow, accompany” → 従えるshitagaeru – “subdue, be accompanied by”

It is pretty clear that the act of obeying or accompanying (intransitive) is the fundamental idea and that compelling obedience or being accompanied is the extended or “eru-flipped” version.

This method is more “feeling-based” and less hard-and-fast than the other rules, but it works easily and intuitively a lot of the time once you have some immersion experience.

And that is precisely why am a little dubious of things like transitive/intransitive worksheets. What will really give you the feel for how words work is meeting them and making friends with them in real contexts, not learning them from lists or worksheets.

The rules I have given here are essentially “force multipliers”. They make it far easier to grasp quickly what the words are doing. That is why I use and recommend them. But they don’t substitute for making real friends with the real words in the real world (whether that “real world” be an office in Tokyo or a fantasy anime).

Also, learning from lists and worksheets that this or that word is “transitive” or “intransitive” may in fact give a false idea of what the words actually do.

Let’s go back to our last example to explain that:

従うshitagau – “obey, follow, accompany” → 従えるshitagaeru – “subdue, be accompanied by”

Shitagau is the “intransitive version” of the verb. The (J-E) dictionaries mark it as intransitive. The grammar books call it intransitive…

But wait! In English it would be mostly transitive, wouldn’t it? You obey someone, follow someone, accompany someone, don’t you?

But on the other hand shitagaeru is thought of as “more transitive” than shitagau because you are causing someone to shitagau. Surely this is closer to “causative” than “transitive”.

And there are a lot of so-called “transitivity pairs” like this, that actually have no real relation to the Western concept of grammatical transitivity.

The moral of this is, don’t take these Western-imposed grammar terms too literally. Sometimes they fit perfectly, other times they don’t really fit at all when you examine them.

If you think in Japanese terms and call them self-move verbs and other-move verbs the whole thing is much clearer. In obeying, following or accompanying someone, you are moving yourself, not that other person. In subduing or being accompanied, you are moving (or causing the action of) the other person.

In truth what Western textbooks call the “transitive verb” of a pair really means “the more suru-like version” and what they call the “intransitive verb” is the more aru-like version. Sometimes this corresponds exactly to Western notions of grammatical transitivity and other times it doesn’t at all.

Understanding this and developing the feeling of real Japanese by immersion makes the Basic Concept “rule” much more effective and intuitive, and puts the whole concept of Japanese “transitive” and “intransitive” verbs into the correct Japanese perspective rather than an artificial Western-textbook one.

How to learn transitive and intransitive verbs

If you want to learn by the immersion-based approach advocated by this site, how should you approach learning “transitive” and “intransitive” verbs?

Don’t try to learn lists of transitivity pairs. That doesn’t serve any very useful purpose. Build your core vocabulary organically, but you will encounter transitivity pairs naturally in the course of this.

Do bear in mind the Three Laws and other rules. Especially, you will soon start noticing: “Ah yes, this word is the transitive すsu-version of that word”. “広がるhirogaru? Yes, that must be the intransitive aru-version of 広げるhirogeru.” You will begin to notice eru-flipped versions and start to get the instinct that meru-versions just feel like other-move verbs.

I recommend keeping one simple “Exhibit A” example of each Law in your mind (such as 出る / 出す for the First Law). This is much easier than remembering it purely as an abstract rule.

By all means leverage the two-for-one advantage of putting both versions on an Anki-card when the opportunity arises, (you may even want to check for a “partner” if a word sounds like, say, the –aru, –su or -meru half of a pair) but bear in mind that if a word is one of those eru-flips not covered by the Laws, your head may be clearer for knowing one of them before you get to the other.

I have used the terms “transitive and intransitive verbs” in this article because they are the usual ones that you find in the textbooks, but also bear in mind that they can’t be taken literally all the time.

If you are starting to think in Japanese, or even if you aren’t, there is a lot to be said for using the correct words, jidoushi and tadoushi – self-move and other-move words. Because that is what they actually are, and the less you clog up your Japanese with cast-offs from foreign grammar the more easily you will understand it.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge