I am Not an Eel was Cure Dolly’s first step in revolutionizing our understanding of Japanese. It now appears as Chapter 2 of Unlocking Japanese and we reprint it here so that you can get a full taste of how Japanese can become simple and understandable once you know how it really works.

I am Not an Eel was Cure Dolly’s first step in revolutionizing our understanding of Japanese. It now appears as Chapter 2 of Unlocking Japanese and we reprint it here so that you can get a full taste of how Japanese can become simple and understandable once you know how it really works.

Here it is! Using the ancient koan of the eel and the diner, the mysteries of invisible Japanese pronouns and the wa-particle are about to be finally unveiled

Enlightenment commences in 3… 2…

私はウナギです

Watashi wa unagi desu

is a common joke among Japanese learners. It is a kind of expression Japanese people often use and the idea is that it literally means “I am an eel”.

After all, watashi wa gakusei desu means “I am a student”, doesn’t it?

What watashi wa unagi desu really means, of course, when said in context (probably in a restaurant) is “I will have eel”. The common Western impression is that the speaker has literally said “I am an eel”, but by a sort of colloquial contraction it is understood in context to mean “I will have eel”. Even the scholarly and usually excellent Dictionary of Basic Japanese Grammar says that “I am an eel” is the literal meaning (an example of how explaining Japanese in English can be a problem even for Japanese people).

So what is the real solution to the eel conundrum?

First of all, let’s look at the way nouns and pronouns are dropped (this is important to our eel, as you’ll see in a minute). This is sometimes considered very obscure and confusing. It isn’t. It is really only doing what all languages do but in a slightly different (and rather more efficient) way. Consider this English passage:

As Mary was going upstairs, Mary heard a noise. Mary turned and came back down. At the bottom of the stairs, Mary saw a tiny kitten.

Is that grammatically correct? Of course it is. Just as correct as saying watashi wa all the time when it isn’t necessary. Would any native speaker ever say it? Of course not.

Why not? Because having established Mary as the topic we don’t keep using her name. We refer to her as “she”. Japanese refers to her as ∅. That is to say, the Japanese equivalent of an English pronoun is what I arbitrarily refer to as ∅. In other words, nothing at all. But that doesn’t mean that the pronoun isn’t there. Only that you can’t see or hear it. It is crucially important to realize that it does in fact exist.

The absence of a visible/audible pronoun is slightly startling to the Anglophone mind, but actually it is scarcely more ambiguous than English. The words she, he and it could refer respectively to any female person, any male person and any thing in the world. They only have any useful meaning from context. Once the thing or person is established, we no longer name it but replace it with a catch-all marker that actually catches what the context tells it to catch.

Japanese works almost exactly the same but without the marker, which is actually not semantically necessary. If a small child says

Mary was going upstairs. Heard noise. Came back down. At bottom of stairs saw tiny kitten.

we are still in no doubt as to what she means. That is how Japanese works. Putting the unnecessary “she” marker in every fresh clause is actually a slight linguistic inefficiency.

What is the sound of no-pronoun?

But – and here is the very important point – there is a pronoun in Japanese. It is a no-pronoun. The vital point to understand is that the invisible no-pronoun works in very much the same way that English visible pronouns work.

If we don’t realize this, we will continue to think that “Watashi wa unagi desu” means literally “I am an eel”. And that is going to make life difficult for us later in our Japanese adventure.

However, in order to reach complete enlightenment on the unagi koan, we need one more piece of understanding. The particle wa.

In beginners’ texts it is often said that the wa particle means “as for” or “speaking of”. And it literally does. The best translation is probably “as for” (which accounts for the differentiating function of wa too – but that is another question).

So

花子ちゃんは学生です

Hanako-chan wa gakusei desu

literally means “As for Hanako-chan, she is a student”.

Note that there is both a noun and a pronoun in that English sentence. The proper noun “Hanako-chan” and the pronoun “she”. It is the same in Japanese. Except, of course, that the pronoun is ∅.

Hanako-chan wa, (∅ ga) gakusei desu

Understand this and you will be a long way toward feeling how Japanese really works.

Here is the golden rule. Always remember it:

The wa particle never marks the grammatical subject of a sentence.

Taking the wa-marked noun as the grammatical subject is what leads to the belief that the diner is calling herself an eel. It turns Japanese inside out in our minds.

The grammatical subject of “As for Hanako-chan, she is a student” is not “Hanako-chan” – it is “she”. “As for Hanako-chan” merely defines who “she” is.

Similarly, the grammatical subject of Hanako-chan wa gakusei desu is not Hanako-chan, it is ∅. Hanako-chan wa merely defines who ∅ is.

Understand this in simple sentences, and much more complex Japanese will begin to form a correct pattern in your mind.

One may think this is splitting hairs, since in this case (and in a large number of cases) the no-pronoun grammatical subject and the wa-marked topic happen to refer to the same thing, and indeed one defines the other. But that is not always the case. And that is the cause of the unagi confusion.

So let us finally return to the eel that has been so patiently awaiting us.

私はウナギです

Watashi wa unagi desu

is often spoken by a member of a party of diners. It means “As for me, it (=the thing I will have) is eel (as opposed to Hanako-chan who is having omuraisu)”. When spoken by a single diner, it still means literally (if you want the literal meaning – which is certainly not “I am an eel”) “As for me (as opposed to any other customer), it (= the thing I will have) is eel”.

You see the desu does not refer to watashi, which, being marked with wa, cannot be the grammatical subject of the sentence. It refers to the actual subject of the sentence, which is the no-pronoun ∅. The no-pronoun – just like English pronouns – is determined by context.

Literally the sentence means

Watashi wa, (∅ ga) unagi desu

As for me, (it is) an eel

What we are talking about here is “what I will eat”. Therefore that is the “it”, the ∅ or no-pronoun, of this statement.

There is no doubt whatever about what ∅/“it” is since either it is the subject of an actual conversation (Hanako-chan has just ordered omuraisu or the waitress has asked “what will you have?”) or it is obvious from the fact that the waitress is a waitress and has approached your table. She has not come to ask you for a stock-market tip. Or if she has, she will say so. If she doesn’t, it can be safely assumed that the unspoken question is “what will you have?”, which determines the ∅ or “it” of the reply. The watashi wa (which can very well be omitted, especially when the diner is not one of a party) is merely distinguishing the person (as distinct from other persons) to whom the ∅/“it” pertains.

Really, it is as simple as that.

Did you know what “it” was in that last sentence? Of course you did – even though it was quite abstract: “the gist of this article, the subject I am trying to explain”.

In Japanese I would have said

こんなに簡単です

Konna ni kantan desu (= ∅ ga konna ni kantan desu)

No written “it”, but just as clear.

From this starting-point, Cure Dolly builds out to show how Japanese can be understood as the simple, logical language that it really is. Read the whole of Unlocking Japanese to revolutionize your understanding of the language. Unlocking Japanese can be read in an evening, but it will simplify and clarify the language for the rest of your life.

I am Not an Eel was Cure Dolly’s first step in revolutionizing our understanding of Japanese. It now appears as Chapter 2 of

I am Not an Eel was Cure Dolly’s first step in revolutionizing our understanding of Japanese. It now appears as Chapter 2 of

Miss Geneviève Falconer once said: “Most English-speaking people would benefit immensely from learning a first language”. The witticism is apt and much appreciated, but in my case it is more literal than it was ever intended to be.

Miss Geneviève Falconer once said: “Most English-speaking people would benefit immensely from learning a first language”. The witticism is apt and much appreciated, but in my case it is more literal than it was ever intended to be.

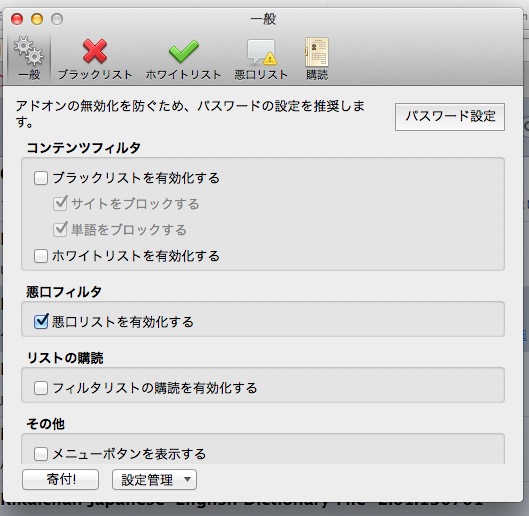

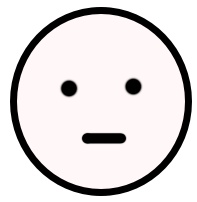

The traditional explanation of the kanji for “monarch”[right], for example, is that of the joining of the three worlds of Heaven, Earth and Humankind. But really anyone conversant with the traditional concept of monarchy would hardly need to be told this any more than she would need to be told that a circle with two dots for eyes and a line for a mouth meant “face”.

The traditional explanation of the kanji for “monarch”[right], for example, is that of the joining of the three worlds of Heaven, Earth and Humankind. But really anyone conversant with the traditional concept of monarchy would hardly need to be told this any more than she would need to be told that a circle with two dots for eyes and a line for a mouth meant “face”. Suppose some scholar were to tell you that the “kanji” to our left – which means face – was actually not originally a depiction of a face, but of a shirt button with holes for the thread.

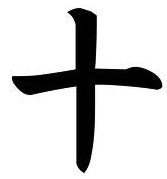

Suppose some scholar were to tell you that the “kanji” to our left – which means face – was actually not originally a depiction of a face, but of a shirt button with holes for the thread. To take one more example, we are asked to believe that the kanji number ten (juu) is unrelated to the essential symbolism of the cross and is merely an “accidental” simplification of an earlier form, influenced by the kanji for a sewing needle.

To take one more example, we are asked to believe that the kanji number ten (juu) is unrelated to the essential symbolism of the cross and is merely an “accidental” simplification of an earlier form, influenced by the kanji for a sewing needle.