Shadowing Japanese is recommended by many people as one of the best ways to learn the language.

There are a few versions of Japanese shadowing around, but they all involve speaking at the same time as a native speaker, saying what she (or he – you should use a speaker of the same gender as yourself) is saying at the same time she is saying it.

Everyone agrees this is difficult, but I suspect it is a lot more difficult for some people than others. Those of us who have very poor short-term memory or lack a certain kind of vocal extroversion can find Japanese shadowing pretty much impossible.

And this is unfortunate because it really is a valuable technique. It doesn’t only improve your speaking. It improves your sense of Japanese rhythm and your ability to hear what a speaker is really saying rather than post-process it into sounds you are more familiar with.

I have recommended using the Amenbo no Uta for these reasons, but it is not a substitute for actual shadowing (though it is a very good supplement to it).

So let’s suppose you are like me and find shadowing to a live speaker or trying to shadow from a text to a speaker in real time prohibitively difficult. Is there a way to get over this problem and get the benefits of shadowing?

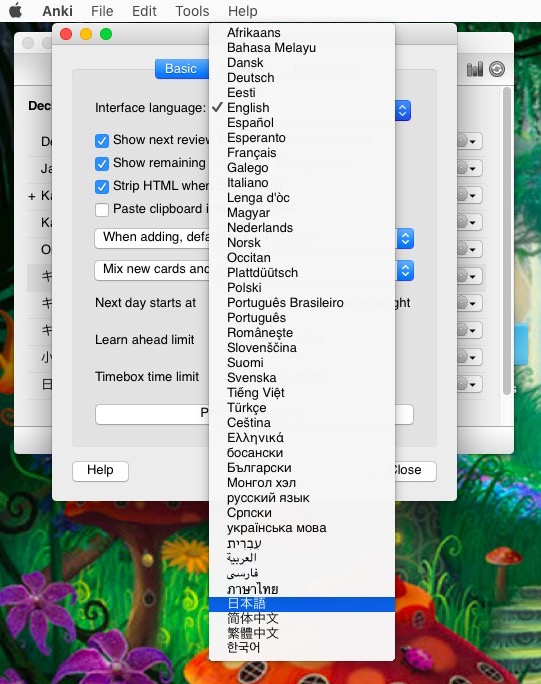

Fortunately there is. I call it “harmonizing” and it involves a somewhat unorthodox use of Anki. You are probably already using anki to build your core vocabulary, and you may be familiar with some of my non-standard applications of the tool.

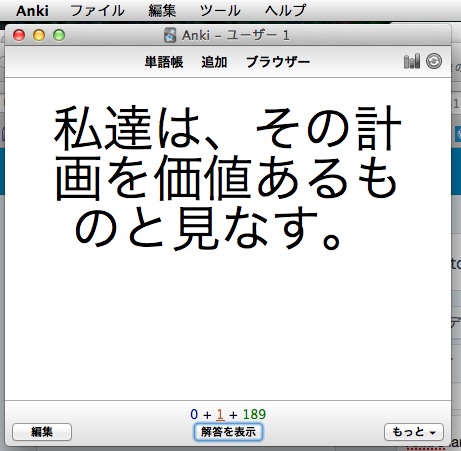

Using Anki to shadow Japanese is even more unorthodox. We are not going to be using it as an SRS tool at all. The only role it plays in Harmonizing is that of a box for throwing up random sentences spoken by Japanese speakers plus text of what they are saying and a convenient one-button method of having them repeat the phrase as many times as you want.

This is why I call it harmonizing. We aren’t trying to shadow long or even medium texts. What we are doing is taking a short phrase spoken by a native speaker and getting used to speaking it in harmony with her. It may take several tries if you are poor at shadowing, but it is a nice contained way of doing it. You will get the sentence with a little practice and be able to say it at the exact rhythm of the speaker.

I aim to do each sentence in perfect harmony five or ten times, then move on to the next sentence. One interesting thing you will find is that some sentences that felt really hard to come to grips with the first time will be easy days later (even with the Anki SRS gap). You have picked up the rhythm of that sentence.

This is super important because the rhythms of Japanese are not the same as English rhythms and that is one of the main reasons Japanese is so hard to hear. By shadowing/harmonizing you are forcing yourself to catch the actual rhythm and pronunciation. With harmonizing you are trying to get your voices to “ring” together like a choir. That won’t happen unless you have the rhythm and cadence very close to right.

Once you have this it becomes easier to pick up what Japanese speakers are saying because your brain is not (or at least is rather less) trying to do what it has been trained to do for years, to translate all vocal noise into English-like sounds. It has become viscerally aware of another kind of spoken rhythm.

How to Shadow Japanese by the Anki Harmonizing Method

Here is the step-by-step guide.

1. Get a deck that has spoken sentences. You will find several in Anki’s shared decks service. Less than there were, since Anki has become more strict about copyright material, but still plenty for your purposes.

2. Start using the deck in the regular way. If the sound is on the back, pass the card immediately. You are not using Anki to test yourself in the ordinary way. If the speaker is the wrong gender or for some reason you don’t want to do that sentence, hit “easy” and make it go away.

3. When you have a sentence you want to work with (you should be able to work with most sentences spoken by someone of your own gender), use the R key to repeat the audio. It may take several tries at first before you get a reasonable harmony. Don’t worry. They are short sentences. Just ganbaru. Don’t despise single-word audio. You can get a lot from shadowing one word exactly right. You will find you can build up to longer sentences.

When you get that satisfying “ring” use the R key several more times to really internalize the rhythm you have now caught.

You are actually training your mouth muscles as well as your ear. There are hundreds of muscles in your mouth and different languages use different ones. You may well find you physically tire quite quickly at first. Don’t worry. It is more important to do a little regularly than to tire yourself with a lot in one session.

4. If you like the sentence and want to shadow it more, hit “hard” to make it come back more often. Remember this is NOT a right/wrong test. Forget everything you know about using Anki when you are harmonizing!

These are the basics of the technique and all you need to know. But let’s have a few

Extra Japanese Shadowing Tips

• It is a good idea to start each session with the Amenbo no Uta. If you can say it reasonably fast, or if you only use part of it, this takes less than a minute. It is not used by just about all Japanese speaking professionals for nothing. It really does help you get your tongue around the sounds of Japanese.

• Things to concentrate on are mora, and the length of “vowels”. I have talked about this at length in the Amenbo article. Remember that もう is two morae, not one syllable. ラッパ is three morae, not two syllables. The Amenbo will help you with this, but as you harmonize, be aware of it. It will be vital to getting that “ring” with your partner’s voice.

• Relatedly, be aware of how very short single vowels are, especially at the end of words. At first, if you get them right, you kind of feel as if you are clipping them off half-way through saying them.

• Try to feel the quality of vowels. Notice, for example, how お is somewhat like a shortened version of the sound we make in “door”, not the one in “hot” or “hoe”.

• Note that the T sound is made with the tongue on the back of the teeth, not the alveolar ridge, as in English, and that just about everything is pronounced further forward in the mouth than in English.

Not More Anki…

Shadowing is a fundamental technique for helping you to truly get Japanese into your blood. But you may be thinking you don’t wnt to take on another time-consuming Anki obligation.

Fortunately this is not Anki in the usual sense. You don’t need to do it every day, and you don’t need to clear your deck. You don’t care if you get a massive build-up. This isn’t SRS, it is your personal shadowing box.

Yes, if you are building a core vocabulary and learning kanji you need a solid commitment to Anki or some other system. But using Anki for Harmonizing or shadowing Japanese doesn’t work like that.

It is good to do it pretty regularly, at least at first, but you are always in control. Do as much or as little as you feel you need. The SRS algorithm that is so important to the long-term learning of Kanji in particular (vocabulary should be at least partly handled by massive exposure) is irrelevant here.

So if you want to shadow Japanese (and you should) but you find the regular methods tie you in knots, here is the key to the magic door.

Use it wisely. Great treasures lie within.