The Amenbo no Uta is sometimes recommended as a way to improve one’s Japanese pronunciation. However, it can do more than that. It can also improve one’s ability to hear and comprehend the language.

But what is the Amenbo no Uta? It is a nonsense poem that is used by just about all Japanese speaking professionals as a daily warm‐up, from news‐readers to voice actors (and very likely politicians too). While it reads like a stream‐of‐consciousness dream‐sequence, there is method in its words, but not narrative method. Its aim is to drill all the sounds and combinations of Japanese.

It runs to a very strict rhythm, and this is particularly important for the Japanese learner.

One of the problems, not only with speaking but also with hearing, is that we post‐process what we hear rapidly and immediately. For first‐language comprehension this is very useful. We are able to hear all kinds of strange accents, mumbled words and distortions and adjust for them, processing them back into the sounds they “ought” to be.

However, when we hear foreign sounds, we process them back to the nearest familiar equivalent, often helped in the case of Japanese by Romaji transliterations, which also represent the nearest English language equivalent. So we hear し as shi, for example (in fact it is neither shi nor si but a sound that does not exist in English). This doesn’t matter too much for comprehension or comprehensibility, though it is good if we can overcome it.

More important is the fact that the English sense of rhythm is radically different from the Japanese, and this does make Japanese very hard to hear. Our brains are attempting to post‐process what we hear into something English‐like that is very different from what we have heard.

That is one great importance of shadowing. It forces us to say, and therefore become aware of, what we are actually hearing, not what our brains want to post‐process it into.

Reciting the Amenbo no Uta can also help with a very important aspect of this: Rhythm. English is a stress‐timed language, while Japanese is mora‐timed. A mora is not actually the same thing as a syllable. This statement sometimes puzzles people, but I believe we can demonstrate here exactly what we mean, using the Amenbo no Uta.

First of all, I would like you to read and listen to the first four verses. They are written in kana. As you may know, every kana corresponds to exactly one mora (ex cept the small versions of the three y‐kana: ゃ,ゅand ょ which always combine with い‐row kana to form single‐mora glides: きゃ, りゅ, ちょ etc.)

Here is the reading, at a relatively slow “training speed”:

あめんぼ あかい な

あ い う え お

うき もに こえびも

およいでる

かき のき くり のき

か き く け こ

きつつき こつ こつ

かれ けや き

ささげ に すを かけ

さ し す せ そ

その うお あさせ で

さしました

たちましょ ラッパ で

た ち つ て と

とて とて たった と

とびたった

I think you can hear the very regular rhythm:

1234 1234

12345

1234 1234

12345

Each mora is a beat of the poem (and you will also find this in most Japanese songs).

So here is why a mora is not a syllable. We have a very good example in the first line:

あかい な akai na (1234). English speakers are prone to pronounce and hear this as a 123 “ak eye na”. Because in English the diphthong ai (often spelled “I”) plus any attached consonants is one syllable, eg. “time”, “mind” “sky”.

In Japanese there are no diphthongs. Japanese あい is not the one‐syllable English sound “I”. It is two morae あ and い. It is the same if a consonant is attached:

かい is か+い: two morae.

あかい is あ+か+い: three morae.

This is why it is important to read Japanese in Japanese script.

Going back to the beginning of the line, we are prone to read あめんぼ (1234) as amenbo (123). It doesn’t help that that is how it is written in Romaji, but we would do it anyway because that is how English works. We post‐process what we hear into something we are used to hearing rather than what we actually are hearing.

So already, unless we are attuned to the rhythm of the poem we have 123 123 instead of 1234 1234 for the first line.

あめんぼ is four kana and four morae. a me n bo. ん is always a mora of its own. Japanese people always think of it that way. If a Japanese person says bangohan to you and you don’t catch the word, she will repeat it slowly and carefully:

ba n go ha n (12345)

pronouncing each mora separately.

Fortunately, for much of the poem morae and syllables are the same, so we are able to catch and hold the rhythm easily. But the places where they aren’t are very important. By using this exercise regularly and getting it into one’s blood, one begins to feel the mora‐rhythm of Japanese. Once one has that, the language becomes more hearable. Naturally the Amenbo no Uta should be combined with listening to regular Japanese (your favorite anime is fine, so long as there are no English subtitles).

To round up a few more common difficulties in these first four verses:

We are prone to hear さしました sashimashita (stung) as sashimashta (1234). This is not exactly the fault of Romaji (though the kana tell us how many morae there really are). Most Japanese speakers suppress the second “i” sound almost completely, if not completely. But even if it is completely suppressed it still takes up a mora.

This is another way morae differ from syllables. A mora does not have to contain much in the way of actual sound. It is a beat, whether fully voiced or not.

When saying the Amenbo no Uta you could emphasize this by pronouncing the word sashimashita with the second “i” vowel fully spoken. However, I would advise against this. It is important to practice giving full mora value to morae with no vowel.

A very similar consideration applies to the small tsu. The fourth verse uses several of these, and each time they occupy a mora (as they always do).

We may hear たちましょ ラッパ で tachimasho rappa de as 1234 123, but if we do, it is because we are not counting the gap between ラ and パ (marked by ッ) as a beat.

Because I am writing this, it tends to sound very theoretical. In fact it is quite the opposite. We are talking about the rhythm of the language. Its very heartbeat. You need to to feel this in your blood, not just know about it.

If you can chant Amenbo no Uta every day with its proper rhythm…

1234 1234

12345

1234 1234

12345

…you can safely ignore everything I have written here. You will be getting the language in a more natural way.

Still, I hope you found it of some use.

Reccomended: Harmonizing – How to Shadow Japanese

The Full Amenbo no Uta

あめんぼ あかい な

あ い う え お

うき もに こえびも

およいでる

かき のき くり のき

か き く け こ

きつつき こつ こつ

かれ けや き

ささげ に すを かけ

さ し す せ そ

その うお あさせ で

さしました

たちましょ ラッパ で

た ち つ て と

とて とて たった と

とびたった

なめくじ のろ のろ

な に ぬ ね の

なんど に ぬめって

なに ねばる

はと ぽっぽ ほろ ほろ

は ひ ふ へ ほ

ひなた の おへや にゃ

ふえ を ふく

まい まい ねじまき

ま み む め も

うめ の み おちて も

み も しまい

やき ぐり ゆで ぐり

や い ゆ え よ

やまだ に ひ を つく

よい の いえ

らい ちょう さむ かろ

ら り る れ ろ

れんげ が さいたら

るり の とり

わい わい わっしょい

わ い う え を

うえきや いど がえ

おまつり だ

PS ‐ there is one line (only one) where the scansion is not regular. Once you have the feel of it you will get a little “glunk” (to use the technical term) on that line. Presumably it was caused by the exigences of getting all the sound combinations into one poem. It really is a 力作, or a tour de force as we say in ‐ uh ‐ English.

I will send an invisible winged Dollykiss to the first person to identify the “odd” line in the comments below.

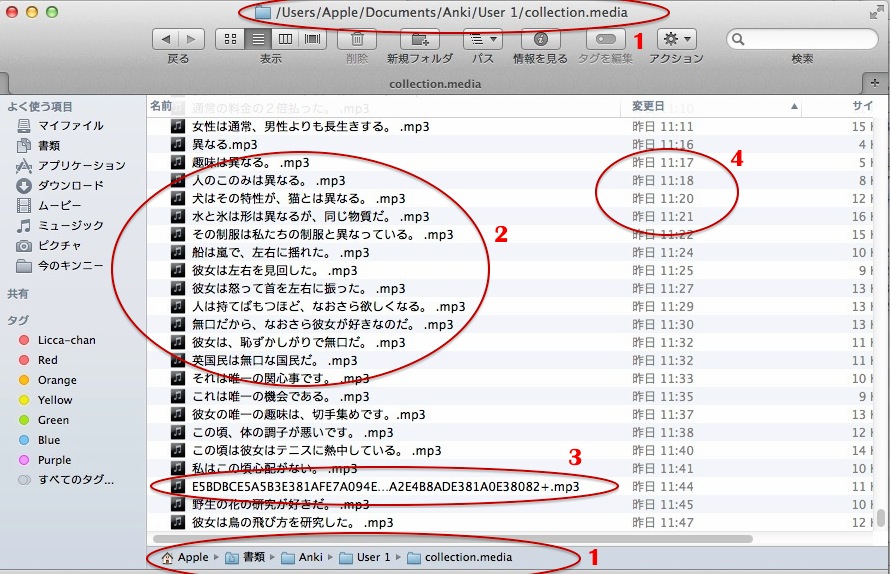

If you click one of these it will give a window like this.

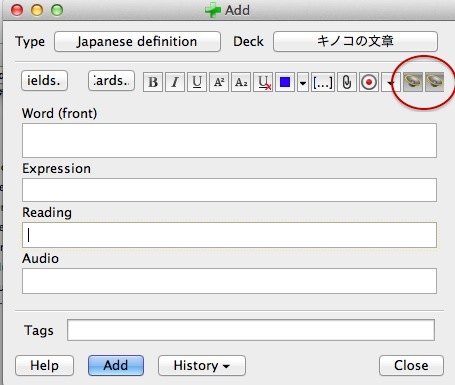

If you click one of these it will give a window like this.