Kawaii Japanese was a simple concept. We wanted to make a Japanese-learning site and community that focussed on kawaisa – a cute, friendly, girly Japanese language site. But it came from a deep and important concept.

To us, Japanese is an adventure. It is a long dive into the deep waters of the Japanese language. To us it is not learning a second language, but learning a new first language. To us language is not just a series of arbitrary noises and marks that have developed meaning. To us, language is a dimension of the soul. And the Japanese language is the soul-dimension we have committed ourselves to enter and explore, not as detached observers, but as children entering a new world.

People learn Japanese for a lot of reasons and from a lot of angles. The reason the main contributors of this site are learning Japanese are probably extremely unusual, but we won’t go into that here. You’ll pick it up in various articles along the way if you take an interest in the site.

One thing that we noticed in our own odyssey was that some of the sites that are closest to our approach and ideas are rather the opposite of our world-outlook. They were (like us) interested in immersion, in making the Japanese language a part of one’s life in a profound way. But at the same time they tended toward a coarseness and deliberate vulgarity and cynicism which is the very opposite of how we think and why we are adventuring into Japanese.

We felt we might not be alone in this. Which is why we began this site.

Japanese is the world we chose to enter because we find it more graceful and lovely, more gentle and pure than what modern English has become. Cynicism has become hard-wired into the English people speak these days. One thing we are seeking in Japanese is the opposite of cynicism. It is innocence.

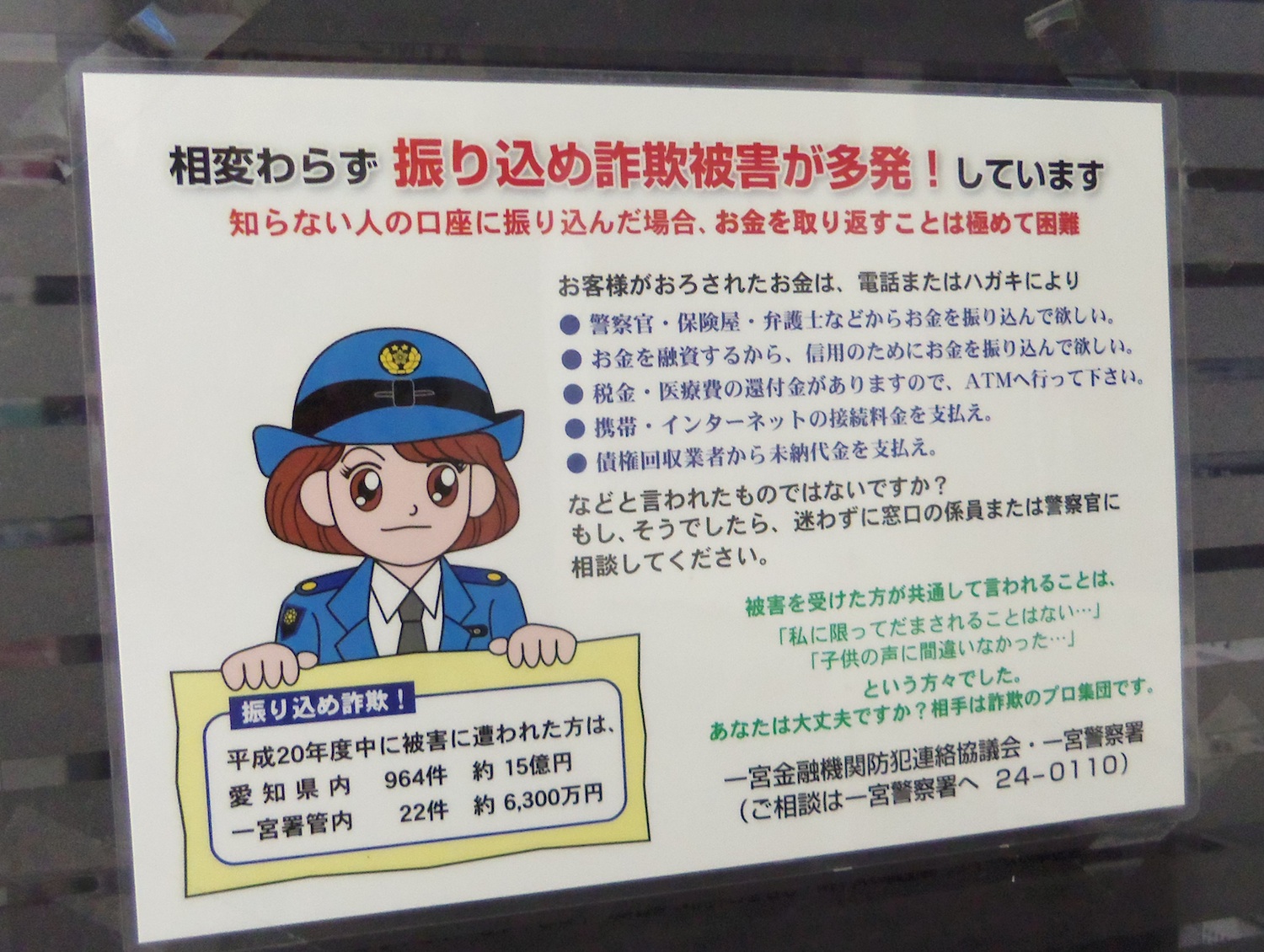

In Japan an important dimension of the quest for innocence, the honoring of innocence, the understanding of the real value of innocence is expressed by the hugely widespread culture of Kawaisa – which is so deeply embedded in Japanese society that it is used to represent not only big companies but the police and armed services.

Not that we were thinking of joining the Japanese police or anything! Or even that we are meaning to say much about how kawaii actually operates in Japanese society. That isn’t really the point. The point, for us, is that kawaii represents a fundamental yearning for innocence and goodness, and that is the yearning we have. And we don’t think we are alone. You aren’t supposed to say things like this in the Western part of the Earth. You are supposed to be cynical and hard and knowing. Well, we aren’t and we don’t want to be, and that is what this Japanese adventure is about.

Now somewhere along the road to starting this site we added the word “profoundly” into our header. There was a reason for that. We have two special angles on the study of Japanese – one is kawaii, and the other is that we want to look into the deeper meanings of Japanese language. We believe Japanese – like all languages – has its roots in ancient and profound wisdom, and some of our articles (probably especially those by Cure Tadashiku) will talk about this too.

Is this something very different from kawaii? Well, on the surface it looks like it, but we don’t think it really is. Kawaii is a modern expression of the timeless desire for innocence and goodness. The wisdom-roots of language connect us to the fundamental realities of being – to the essential thisness of things and we believe that the underlying truth of existence is fundamentally pure and innocent.

This part may appeal to you or it may not. It doesn’t matter. If you are learning Japanese, or just interested in the language, and you love kawaisa, this is the place for you. Please make yourself at home.