I was a little hesitant in writing about my kikitori Japanese listening sentences method, because it may be somewhat idiosyncratic. However, it is working well and friends have taken some interest, so I’ll go ahead.

I was a little hesitant in writing about my kikitori Japanese listening sentences method, because it may be somewhat idiosyncratic. However, it is working well and friends have taken some interest, so I’ll go ahead.

I have read about the 10,000 sentences method of Japanese learning which is recommended by some immersion-inclined sites. Frankly, I could never fully understand it — but then I am just a doll. I fiddled with it for some time and never really got to grips with it.

I did, however, like the idea of learning Japanese in sentences rather than just words. After all, that is how children learn language, and it gives one the feel of what just “sounds right”, rather than merely knowing grammar rules. I am by no means saying one shouldn’t know grammar rules — often one needs to — but I have always argued that grammar is a quick-and-dirty shortcut by which adult learners half-learn a language from the outside rather than actually knowing inside what feels right. Shortcuts can be good. They can even be necessary. But you don’t know a language till you can feel it. You only know about it.

My new assault on the sentences method came about partly as a result of my looking for new ways to improve my kikitori — Japanese listening. I started turning the sentences into digitized speech and putting them in Anki. I would review with my eyes shut and only count myself correct if I got the sentence first time without looking. If I couldn’t, I would give it a second hearing, and if I still couldn’t get it I would open my eyes to see the Japanese text. Only as a last resort do I turn the card over to see the furigana. This rarely happens (after all I can both see and hear the text if I need to open my eyes). The very last resort is to scroll down to where I have (sometimes — when I think I might need it) hidden a translation. This I try not to use and rarely do.

There is a second phase to this method, and that is putting the sentences on an MP3 player. I then play them on a random loop in any spare times (when cooking or walking, for example, and often when resting). I use this a lot, which means I get a lot of exposure to the sentences.

I put a three-second gap between sentences. This is the most my player allows (annoyingly, I don’t think iPods have a means of doing this at all). This gives me a little time to think about a sentence after hearing it, and I think this is important. It is true that in the wild you don’t get any thinking time. But if you are at the stage when you can’t catch much in the wild (in anime or regular non-foreigner-directed conversation), this is what you need in order to get there.

In those three seconds you do certain things and one of them in particular is, I believe, fundamentally important to kikitori or hearing Japanese (or any other language). You correct what you hear. In our familiar language I believe we do this all the time. We hear the word “bubble”, realize that doesn’t fit the sentence we are hearing, and correct it to “double”. We hear the word “wise” and correct it to “wives” (or if we actually don’t understand the context, we don’t — which is why so many people make the blooper “old wise tales” in writing — Google finds over four thousand instances of “old wise tales”).

This common slip (and many others) underlines my point. It really isn’t easy, even in one’s native language, to tell “wise” from “wives”. Ninety-nine percent of the time we understand what the sentence should be and correct mishearings so fast we don’t even know we’ve done it. It is one of the key subliminal skills that makes kikitori — in any language — possible.

With a three-second gap between sentences, we are able to perform this correction-hearing in slow-ish motion, which, at this stage, we need to.

Now, as I have pointed out before, language consists to a very large extent of set phrases and collocations. Words go together in the same groups most of the time. That is a large part of the reason that kikitori is actually possible in any language.

Hearing sentences and auto-correcting (in slow motion at first) lets one go through the same process a child goes through. She hears words together. At first she mispronounces them, and even when she knows what a common word-group means she may not fully understand what the component words are. Slowly it all starts to make sense.

During sentence-listening we think we hear “kaishite”, for example, and realize it must be “taishite”. We also start to get the feel for the fact that in hundreds of similarly-constructed sentences we will hear in our Japanese-language life “kaishite” is actually going to be “taishite”. After a while it won’t even matter, because just as in reading we don’t need to see (and don’t, as studies have shown, even look at) all the letters, so in kikitori we don’t need to hear all the sounds. We get the pattern and fill in or auto-correct the gaps. If we don’t know or fully understand a phrase (such as “old wives’ tales”), even in our first language, we can’t auto-correct and we may go through life hearing it wrongly, as many people in fact do.

The vital point to grasp here is that while our natural, “naive” view of native-language kikitori is that we hear correctly and therefore understand, to a large extent the reverse is true: we understand and therefore hear correctly. Of course both are going on at once, and it is the interplay of the two that makes language-understanding possible.

With one phrase (like old wives’ tales) mishearing doesn’t matter very much. In fact we end up knowing what the phrase means even while consistently mishearing it. But when, in Japanese, we are faced with dozens of phrases that we can’t auto-correct, or can’t auto-correct quickly enough to keep up, then we can’t understand what is being said.

So the three seconds between sentences gives us a kind of middle ground. Doing the sentences in Anki we can ponder the sound at our own pace. In the wild we have almost no time. On the MP3 player we have three seconds to auto-correct anything in the sentence that needs it as well as to muse on the grammar, realize, perhaps on the 30th hearing, “ah, so that‘s why…” and so on.

These are all things a child does. Those of us who grow up continually pondering the ins and outs of language are probably more childish than odd. Children have to do a lot of that for the first several years. Some of us just never stop.

There are many important and interlocking benefits to this sound-sentence method. When we learn vocabulary via Anki, we only know the definitions of words — not how they are actually used. Now when I am going through my vocab Anki I am continually stopping with “that one needs a few sentences”. Once I have become familiar with several sentences using the word, I am much clearer on its range of uses and its nuances. I am also much less likely to forget the word.

In doing all this we are going through the process a child goes through. We are learning how words fit together, what they imply, what their near neighbors are likely to be in a sentence. We are also building up a fund of examples in our mind which we will use, sometimes consciously, but often — and this is where language starts to become natural — unconsciously, to compare with new sentences and new uses of the same words in different contexts. You build up your feel for the language. You start to hear what “just sounds right” without necessarily knowing why.

Surprisingly, the hearing sentences can even help with kanji, since one will sometimes in the Three Seconds think「あぁ。それは緊張の緊ですね」(“Ah, that’s the 緊 kin of kinchou, isn’t it”). Because that is part of how Japanese words fit together and mean what they mean.

Currently I am at 1,600 sentences using this method and I am finding it extremely useful, not only for kikitori but for every aspect of Japanese.

The “throw ’em in at the deep end” school may complain at the three seconds recognition-time, but I am not suggesting that sentences should be our only listening practice. Full-speed native Japanese materials should definitely be used. But using this method, I think you will find that your ability to process that full-speed Japanese progresses a lot more rapidly.

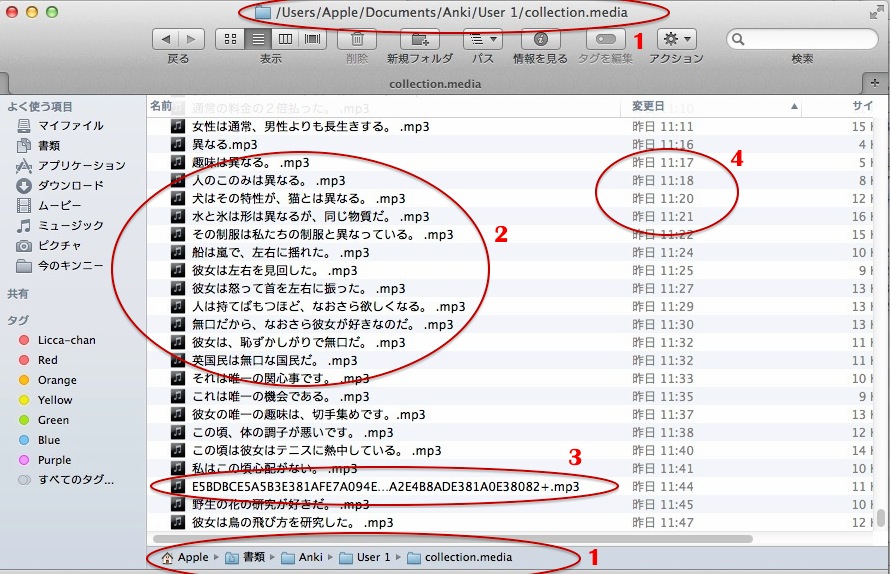

How do I get spoken sentences in Anki? How do they actually sound? How do I get them to my MP3 player? Find all the answers in our sister article on the technical tricks of the Japanese-listening sentences method. It’s easier than you think – even a doll can do it!

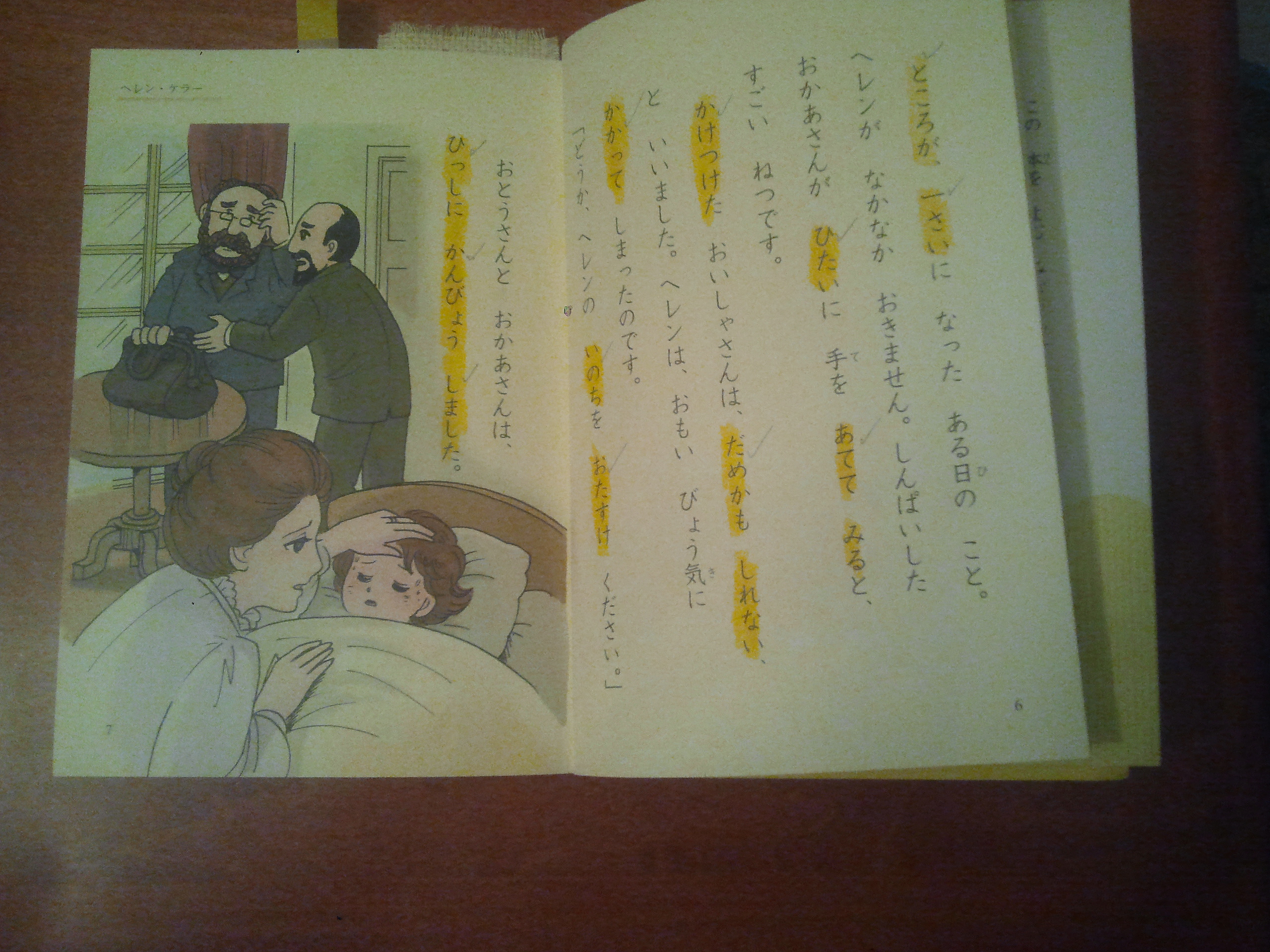

I think I understand why this is working for me. When reading in English, I must automatically filter out words I do not know, gleaning the meaning from context from the words that I do know. In Japanese, that is hard to do. To begin with, one’s eyes must work completely differently. Japanese books are written right to left and vertical. That in itself is an adjustment. Also, Japanese generally does not put in spaces for words, and it is rather fluid as to where words begin and end. Furthermore, Japanese grammar and sentence structure is quite different from English. I think that these differences make it hard to use strategies one naturally uses with English without additional help.

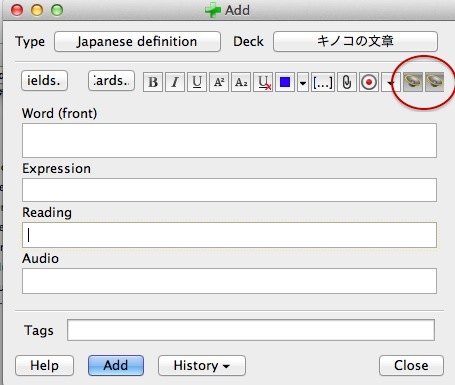

I think I understand why this is working for me. When reading in English, I must automatically filter out words I do not know, gleaning the meaning from context from the words that I do know. In Japanese, that is hard to do. To begin with, one’s eyes must work completely differently. Japanese books are written right to left and vertical. That in itself is an adjustment. Also, Japanese generally does not put in spaces for words, and it is rather fluid as to where words begin and end. Furthermore, Japanese grammar and sentence structure is quite different from English. I think that these differences make it hard to use strategies one naturally uses with English without additional help. If you click one of these it will give a window like this.

If you click one of these it will give a window like this.