There are two ways of going about learning Japanese: immersion and study.

They are not, of course, mutually exclusive, but I am coming to the conclusion that they constitute two very different “cultures” and relationships with the language.

This feeling was recently confirmed by an article on a well-known Japanese-learning site entitled “What Would Happen if Your Japanese Got Too Good”.

The question was essentially: would you be bored if you “finished learning” Japanese? The very fact that the question was asked is interesting, and so were some of the replies. “There is always more to learn: old Japanese, obscure kanji etc.”; “There are plenty of other languages to learn” etc.

The site in question is one that encourages an “RPG” approach to learning Japanese and likens levels of Japanese skill to levels in a game. In one way this is making Japanese learning fun, which I am all for. On the other hand, it is what I would call “meta-Japanese” fun. The fun of this approach is in “learning Japanese”, not in Japanese itself. This seems to go hand in hand with the fact that the site is over 90% in English and essentially devoted to “meta-Japanese” English discussion.

Now I want to make it clear that I am not criticizing this approach. It works for a lot of people. The site is a very good one and I have great respect for its founder. However, it is an example of the “two cultures” that I am speaking about.

The article in question underlined what I have been thinking for a long time. That “learning Japanese” can easily become an end in itself. Again, I am not criticizing. If studying Japanese is your hobby, please enjoy it. It is undoubtedly a good hobby to have.

It just isn’t my hobby. I have never found much commonalty with the “language-learning community” because I am not interested in language learning. I am in love with Japanese. I want to dive into Japanese and live Japanese. I regard Japanese as my language, not “a language” I am “learning”.

What would happen if I “finished learning” Japanese? Well, what happened to you when you “finished learning” your native language?

Think about that for a moment. When did you “finish learning” your native language? Were you ever consciously learning it at all? Did “learning” it matter to you? Or were you just interested in getting on with life: watching movies, playing games, reading books, talking with friends?

Because that is my interest in Japanese. I am simply interested in getting on with my Japanese life. The fact that I have to “learn” it is just something that gets in the way.

It isn’t a bad thing, it’s just a thing. Like the small child who struggles to express her thought in her own language, or the older child who wants to read a book that has a lot of words and expressions she doesn’t understand. We “learn” by getting over the problems life throws in our path.

But “learning Japanese” isn’t the game to me. The game is the game. The book is the book. The movie is the movie.

A famous Internet personality founded what is broadly called “Immersion learning” in Internet circles today. He would write at length about how you don’t need to study you just need to dive into Japanese and “get used” to it. You just need to have fun and learn naturally. He would become very voluble (and at times a bit vulgar) about this.

And I have to say that (minus the vulgarity) I agree with every word he said along these lines. The problem is, he didn’t believe it himself. And neither do the many people who currently follow some version of his approach.

While he preached immersion, sometimes quite ferociously, his recommended practice was something else altogether.

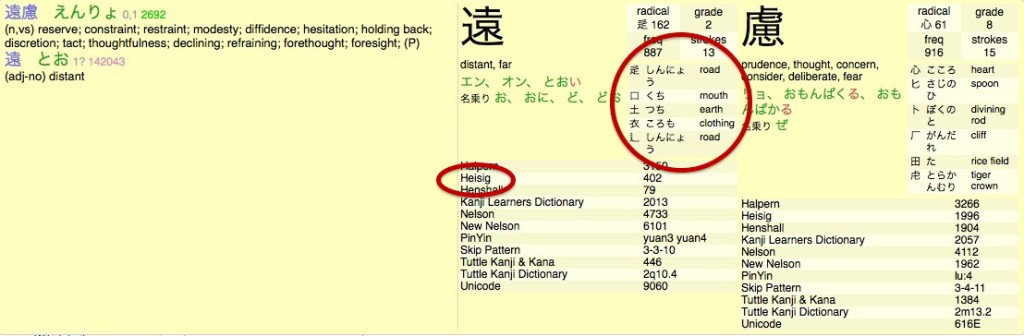

What he actually said one should do is learn kanji via the Heisig Method, which essentially involves learning many hundreds of kanji “blind”, without knowing a single actual word of Japanese. Heisig-sensei himself likened it to putting oneself in the position of a Chinese student who begins knowing no Japanese but a lot of kanji.

The other arm of this method was learning 10,000 sentences using electronic flashcards (Anki). Oh and while you’re at it, do a lot of passive listening to Japanese audio.

Is this unfair? A little, but it is essentially the case. What starts off (and I have no doubt this person was sincere) as an “immersion” approach becomes in practice a massive program of abstract study.

Now I agree that pure immersion from day one is inadvisable. We do recommend learning the basics of grammar and continuing to learn grammar as you go along.

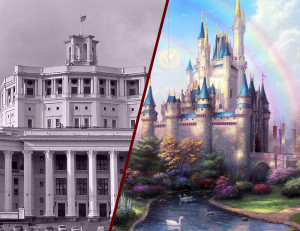

Like the site mentioned at the beginning, we do bring the RPG analogy to Japanese, but in a very different way. Rather than the RPG being a meta-Japanese game of “learning Japanese”. We liken Japanese itself to a huge, complex RPG, and we liken abstract learning to the game’s huge manual.

We recommend reading the introductory tutorial chapter of the manual, just to get enough information to get started, and then diving into the game itself, learning by playing and referring to the rest of the manual as and when necessary.

We do not recommend a long preparatory phase with the goal of using Japanese somewhere at the end of it. We do not recommend hundreds of hours of kanji study, thousands of sentence flashcards or extensive textbook study. We recommend spending most of that time on actually using Japanese. You will need some grammar help, and you will need Anki flashcards for learning kanji, though you will be doing it organically, learning kanji as you encounter them in real words.

Essentially, at every point after the first few months of getting kana and basic grammar under your belt, you are using Japanese first and only “studying” as and when you need it as a support to your real-life use.

In this actual immersion approach, using Japanese is primary. Meta-Japanese elements (study, flashcards, English grammar explanations and the rest) are exactly what the word meta implies. Something on the side of your real Japanese life.

Now to be clear, I am not for a moment attempting to disparage all other ways of learning. There are fundamentally two approaches, and both of them work.

Ours isn’t new. We didn’t invent it. We did pioneer some of the ways to do it via the Internet, but the world is in fact full of people who went to places where other languages were spoken and learned them (at least the spoken versions) just by being there and using them. The true “immersion method” is as old as language itself.

The “study-first” approach isn’t quite so old but it has a long, long pedigree.

We are not claiming that true immersion is faster than study-first (no genuine method is all that fast) or easier than study-first (no method is easy). Which is fastest and most efficient depends on who you are, how you learn, and what your priorities are.

The real point is that these are two very different approaches. Two very different relationships with the process of acquiring Japanese.

Many people thrive on study. Many others burn out and give up before they get anywhere near the “goal” (whatever that actually is).

Many people love raising their levels by study (the idea of treating them as RPG levels was inspired).

True immersion learners probably have no idea what their level is (I know I don’t). On the other hand, they don’t much care. They are more concerned with whether they can enjoy this anime, read that book and express the idea that is in their mind.

I tend to think of study-first and immersion as the “Classical” and “Romantic” approaches respectively. If you want to pass exams the Classical approach is probably better. If you have a methodical mind you may well find it better (though I know some very methodical people who use true immersion).

But:

If your love of Japanese is such that you want to dive into its warm waters and swim toward the golden sunlight…

If Japanese feels like your true language, not just “a language” to “learn”…

If you see mechanics of learning as just a necessary evil and what you want is to embrace Japanese herself…

If you are determined enough to climb the sheer cliff-face of real use, rather than use the long stone steps of study…

Then the Romantic method will call to you. And here is how to get started.

(If you need help with starting on the Romantic path to Japanese, you might want to go here)