You can learn Japanese online in a fast, fun simple way.

You can learn Japanese online in a fast, fun simple way.

You can create your own “immersion environment”, surrounding yourself with Japanese media. The internet makes this possible in a way it never has been before.

You can minimize book-learning and drills, and dive right into the wide world of actually using and enjoying Japanese.

Let’s be clear. We aren’t selling anything and we aren’t promoting some kind of “get-fluent-quick” scheme.

We are simply explaining the key immersion techniques we use to learn Japanese online naturally and organically. Plus the simple “secret” that ties everything together.

Our approach to learning Japanese is pragmatic. We recognize that people learn differently and that “one size fits all” approaches actually only fit some people.

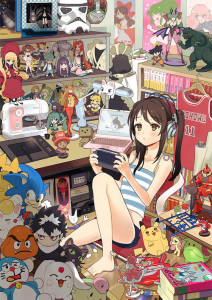

Our approach is based on immersion. It centers around a core of anime. We recommend a number of other techniques that surround, support and branch out from this core.

This site has a lot of information. So on this page we are going to boil it down to the very basics. Not everyone will use every technique we recommend. Those who do will adapt some of them. That is fine. One size does not fit all.

But if you want to learn Japanese online the way we do, here are the core techniques that work together.

There are four core techniques. And then there is the fifth core secret that makes them work exponentially more effectively.

This is just an overview. We also give links to more detailed explanations of exactly how to do each step.

Learn Japanese online: the Core Four +1

1. Grammar. If you don’t know basic Japanese grammar you need to acquire it. Just the basics to begin with. Here is how to go about it.

Some immersionists say you can pick up grammar from context the way a child does. You can, but we would say that doing so is neglecting the only real shortcut you have as an adult (or teen) learner and making life much more difficult for yourself.

Learning grammar is not learning Japanese. It is learning about Japanese. But acquiring the basics gives you an important head start when you start actually learning Japanese online. Learning the only way you can learn a language (as opposed to learning about it). By actually using it.

And you can give yourself an even bigger head-start by reading and applying the secrets in Unlocking Japanese, which tells you the things the textbooks don’t, and helps you to get a grasp of the really simple structure of Japanese. You can read this small book in an evening, but it will make Japanese easier for the rest of your life.

But don’t worry. You don’t have to (in fact you shouldn’t) try to “finish grammar” before you start really using Japanese. You are going to start using Japanese very soon. Much sooner than with any other approach. Because the second core technique is:

2. Watch anime!

All right, this isn’t as easy as it sounds. You are going to be watching anime in Japanese with subtitles. Japanese subtitles. It will be tough at first. You will be looking up nearly everything. But that stage passes fairly quickly if you ganbaru.

You aren’t taking lessons. You have set out to learn Japanese online. And anime is going to be your university. You are going to learn vocabulary, kanji and grammar and nearly everything else from anime and looking things up that you encounter. They are going to stick better and make sense quicker because you are encountering them live.

How does this fit in with the fact that you are (at the beginning) still learning basic grammar? Much the same way as if you have a game with a thick manual.

You can plow through the whole manual before you touch the controller. For most people it is more effective to read enough to get started and then start the game, while continuing to read the manual. The complicated parts of the manual make a lot more sense when you are actually experiencing the game.

When you are ready to begin to learn Japanese online through anime, click here!

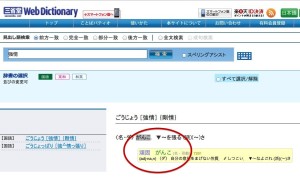

3. Use Anki for vocabulary. Don’t use vocabulary lists, (beyond the very basic first few hundred words) but enter new words as you encounter them in your anime etc. Some immersionists say you should only enter sentences into Anki, not words. This is a valid technique. But it is based on the premise that you have learned kanji via the RTK method. We won’t go into that here, but it involves months of learning all the kanji without learning a single word or a single pronunciation. Just kanji. This does work (for some people), but it isn’t how we go about things. We say, learn words, not kanji.

This means you learn the kanji along with the words, and Anki is a really wonderful tool for doing this. If you don’t want to use Anki, you will need another strategy for memorizing vocabulary and kanji. That’s fine. Mixing methods is not a bad thing. But remember that you can’t just leave this core technique out. If you are going to drop it, you will need another strategy for memorizing vocabulary and its associated kanji.

4. Fill your ears and your life with Japanese. Put the soundtracks of the anime you have watched on your mp3 player. Keep it playing any time there isn’t a huge reason not to (turn it down, not off). Or have Japanese television in the background. Switch your computer’s OS to Japanese as soon as you can just barely handle it.

People differ. Not everyone will want to go as far as we do. I make Japanese my default language. I do my best to keep my inner monologue in Japanese. I only use English when there is a very good reason to do so (like writing this article). If I can’t watch something in Japanese I can’t watch it. If I can’t play a game in Japanese, I can’t play it. It’s as simple as that.

These four are important interlocking techniques. But there is a vital fifth element that holds them all together and makes them work exponentially more effectively:

+1. Make Japanese your language at least in certain areas of your life. This is the One Ring that binds them all. Japanese should not be a “foreign language” to you. It should be your language. You should not be “practising Japanese”, you should be using Japanese.

You already started this with anime. You aren’t playing with textbooks for foreigners (we do recommend learning basic grammar, but only as a quick and dirty shortcut to truly using Japanese). You are watching anime by native Japanese people for native Japanese. It is a struggle at first, but you are doing it. When you use your computer, tablet or smartphone, you are looking at Japanese menus. Japanese isn’t some exotic “other” language. It is part of your life.

So far so good. But there are two halves to language. Input and output. Language is a means of communication. If you want your mind to take Japanese seriously as real language (rather than a limited-area “game-language”, like algebra) you must be using it to communicate inward and outward.

The outward part is admittedly more difficult to arrange. This is partly why it is often ignored.

It is also ignored for exactly the same reason that it is so important. The mind of an English speaker regards English as Language, and Japanese as “a language”. For that reason just about every forum about Japanese learning is in English.

The minute you put down your textbook or manga and want to discuss it, what do you do?

Naturally・・・

You discuss it in Language. Real Language. Not a “foreign language” like Japanese.

And that is the final secret. The One Ring that binds them all. Japanese has to become Real Language. To me Japanese is Language per se, the language I use except when I absolutely have to use another language. You may not want to go that far, but you do need to have “zones” of your life in which Japanese is Real Language.

But… is this the right way for you to learn Japanese online?

We said from the start that one size does not fit all. What we have written above is a bare-bones guide for our system to learn Japanese online. There is lots more on this site to fill in the gaps, and we are adding to it all the time.

But is this the right way for you to learn Japanese online?

Here are a few questions to ask yourself:

Do you love Japanese? This is an immersion method. It involves (surprise!) immersing yourself in Japanese and giving Japanese a part of your heart. Maybe a big part (that is up to you). If you don’t love Japanese this isn’t the approach for you. If you don’t that’s fine too. I learned some French but I didn’t love it enough for immersion.

Do you want to pass exams? This isn’t an academic approach. You will be learning Japanese “from within”. If you want to learn Japanese online in order to pass exams, some of our techniques may still be useful but you will probably also need a more “by the book” approach.

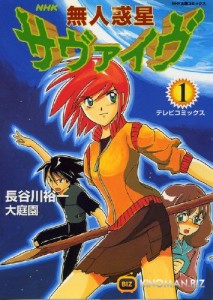

Are you kawaii? Silly-sounding question, but there is a reason for it. We didn’t think we had built our techniques around kawaisa, but in one respect maybe we did. Especially in the early stages you need to use material (anime etc) aimed at children. And the whole point of this technique is that you are doing what you enjoy.

You don’t have to be a full-fledged member of the “kawaii crowd” to use these methods. There is a lot of children’s material that is regarded as classic and loved by even “sensible” adults, but if you really can’t enjoy substantial amounts of material accessible to children (and some people can’t), then the methods as they stand may present a problem to you. You could ganbaru ahead and do it in a spirit of study. But we don’t recommend that. The whole point of this approach is that you are using, not practicing Japanese. Doing in Japanese things that you might be doing in English – even if slowly and haltingly at first.

All right. Assuming that none of these things presents a problem to you: is this the way you want to go? Immersing yourself in Japanese, making it your Language at least for part of your life?

If it is, welcome to the site, and welcome to the select family of second-mothertongue Japanese learners. Even if you only know a few words right now, if you have set your foot on the Way in earnest, you are one of us.

On the other hand, if you want to cherry-pick and just take a few techniques that interest you, be our guest. If even one page helps you a little on your journey to learn Japanese online, we are happy.

To get you started…

This is how to learn basic grammar

This is how to learn Japanese through anime

This is how to build a core vocabulary

This is how to get started with Japanese immersion

This is how to learn Japanese online even if you don’t have a penny

And this is where to come to join the Japanese conversation

See you there!