In the previous article on modern language acquisition theories, we learned how Universal Grammar forms the basis for a child’s initial acquisition of language and generally how that acquisition actually works. Now we can turn to the practical application of the science.

What do these language acquisition theories mean for the language learner?

First, they mean that age is not any kind of a barrier to language learning. After the age of around ten you can learn language equally well at any age. The deciding factors are motivation, amount of study, degree of immersion etc., but not age.

The current language acquisition theories also mean that you will probably not become fully “native” though you may get very near it. They also tell us what the key to this is:

The more you can map your target language onto Universal Grammar rather than onto your first language, the nearer you can become to native.

Now there is a balance here. Especially in the early stages, learning via a known language is a very important short-cut. Remember that contrary to popular belief, small children do not learn language quickly. The number of “study hours” it takes a small child to be able to express herself even rudimentarily is very large indeed. By mapping onto your already-acquired native language at first you can and do cut down this time radically.

Learning grammar rules, as I have often said, is a quick-and-dirty shortcut to learning language. But it is a shortcut and it does work (here is how to go about it efficiently without getting bogged down in it).

Pseudo-immersion methods, like Rosetta Stone, which try to replicate the small-child-learning process fail for a number of reasons: there is no human interaction, it is not done for every waking hour, but primarily they fail and must fail because the user already knows Language. Whatever happens, she will be mapping what she learns onto her native language—just doing it very inefficiently. At the end of many, many hours she knows a lot of nouns, some verbs, and almost no grammar. If she doesn’t give up at that point, she will, very wisely, invest in a grammar textbook.

So do our language acquisition theories deny the possibility of immersion-learning for adults and older children?

Absolutely not. But these, I believe are the conditions:

1. If you can find a genuine 100% immersion environment—all Japanese all the time with complete isolation from your own language—then absolutely go for it. I envy you. You will learn even with no theoretical teaching—though it will take a long time and will actually be much faster if you have mastered basic grammar first. But having said that, it is probably the best way to learn.

2. Failing that, what can and should you do by way of immersion, and how will it work in accordance with our language acquisition theories?

Remember that our aim is, as far as possible, to map Japanese onto Universal Grammar and not onto English. You should start by learning the grammar through the medium of English (or your native language) because that quick-and-dirty shortcut will give you a big head-start once you begin the real thing.

What is the real thing? It will vary from case to case, but our aim is to think in Japanese, not to think in English and “translate” Japanese back to ourselves. To this end, we should:

a. Imbibe native materials (not for-gaijin Japanese) as soon and as much as possible. I have talked about how to do this via anime. Personally, I do not have any recreational activities in English. Japanese to me, outside of necessary English communications (like this one), is not “a language” but Language per se. If I can’t watch an anime in Japanese (with Japanese subtitles), I can’t watch it. If I can’t play a game in Japanese, I can’t play it. If I can’t read a book in Japanese, I can’t read it. I don’t allow myself any recreational English activity.

b. Talk in Japanese every day if you possibly can. Whether it is with Japanese friends or other learners. Some people worry about talking Japanese with non-Japanese people, feeling they may “learn wrong” or pick up mistakes. If you are doing a. you should be getting exposed to a lot of correct Japanese through that. But I also believe that even if you are picking up or cementing in some incorrect language that is not nearly as important as the fact that you are using Japanese regularly. Small children don’t always speak correctly, and often their conversation is with other children who don’t speak correctly. But they do use the language because it is, for them, Language per se—the only means of communication. So it should be when you speak Japanese: even if you both know English, if you can’t say it in Japanese, you can’t say it.

Ideally, it is good to have practice partners with whom you only ever communicate in Japanese. This is important not merely because it extends the amount of time you spend speaking it. The most important element is a subtler, but vitally important, psychological one. You are building a human relationship in which Japanese is the only language—Language per se. Language is the basis of our human relationships, and human relationships are the basis of our initial acquisition and continued use of language.

You see the pattern here. What you are doing is carving out areas of your life where Japanese is not a language but Language per se. You are not practising Japanese, you are using it. If you want to say something to your Japanese-partner friend you have to say it in Japanese because there isn’t another language. If you want to see a movie or play a game, you have to use Japanese because there isn’t another language. Your limitations in Japanese are your limitations, period—at least for the areas of your life that have become Designated J-Zones.

c. Think in Japanese. This is probably the hardest part but also the one that will most effectively map Japanese onto Universal Grammar rather than onto English in your mind. You need to begin putting your internal monologue into Japanese. If not permanently, then at least for designated periods. While this is difficult, it is very possible. You can “dethrone” English from its place as your thinking-language though it takes a lot of ganabaru and a spirit of taihen da kedo zettai ni akiramenai (I definitely won’t give up however tough it gets).

And it will get tough. English will try to hang on to its position as your representative of Language per se—or Universal Grammar—like grim death. Inch by inch you will have to force it out. The more you do this, the more your “first thought” is in Japanese, the more you are mapping Japanese to Universal Language directly rather than to Universal-Grammar-via-English.

By these methods you are forcing your mind, at least to some degree, to map Japanese to Universal Grammar (its root language model) directly rather than via English. Thus you will be using language acquisition theories to your advantage and absorbing and using the language in the most natural manner.

NOTE: Since writing this I have discovered that learning to think in Japanese is much less difficult than I made it sound here if you use the method I recommend. I don’t know if this will work for everyone but it has certainly done wonders for me.

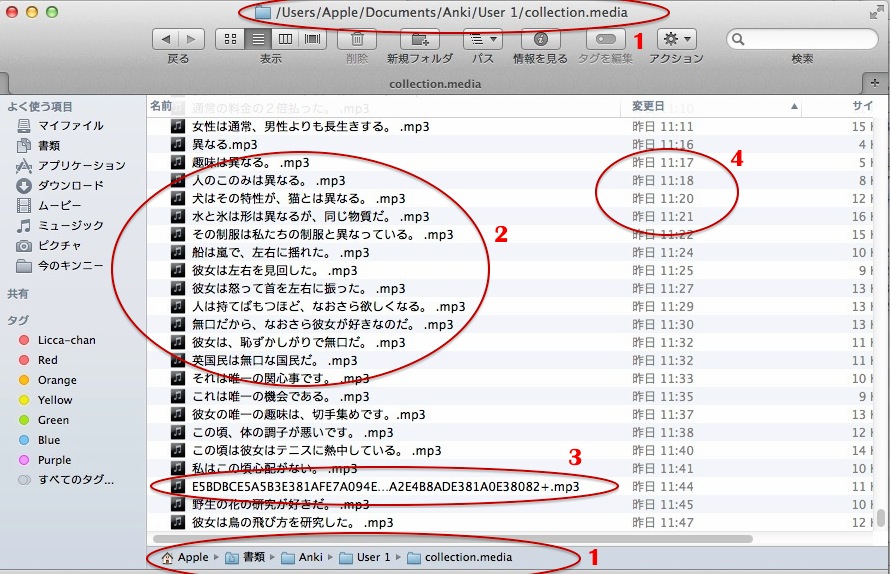

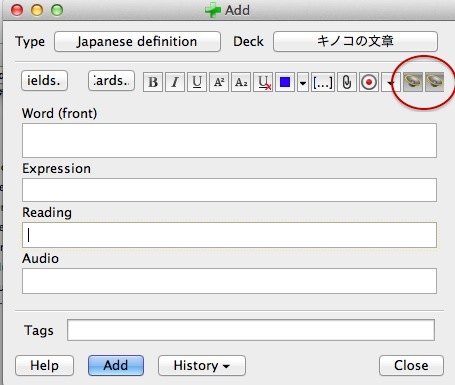

If you click one of these it will give a window like this.

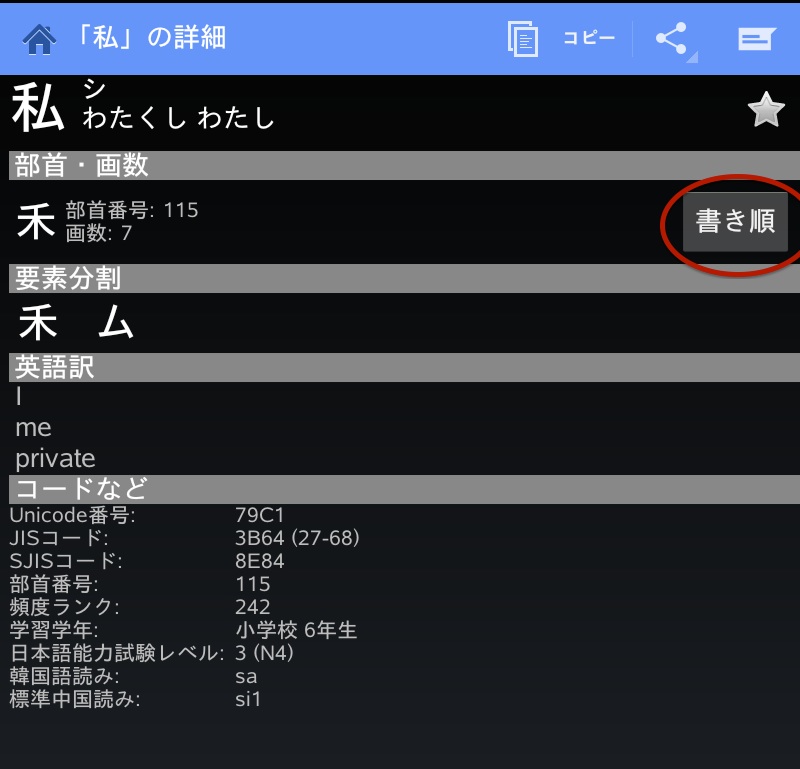

If you click one of these it will give a window like this.